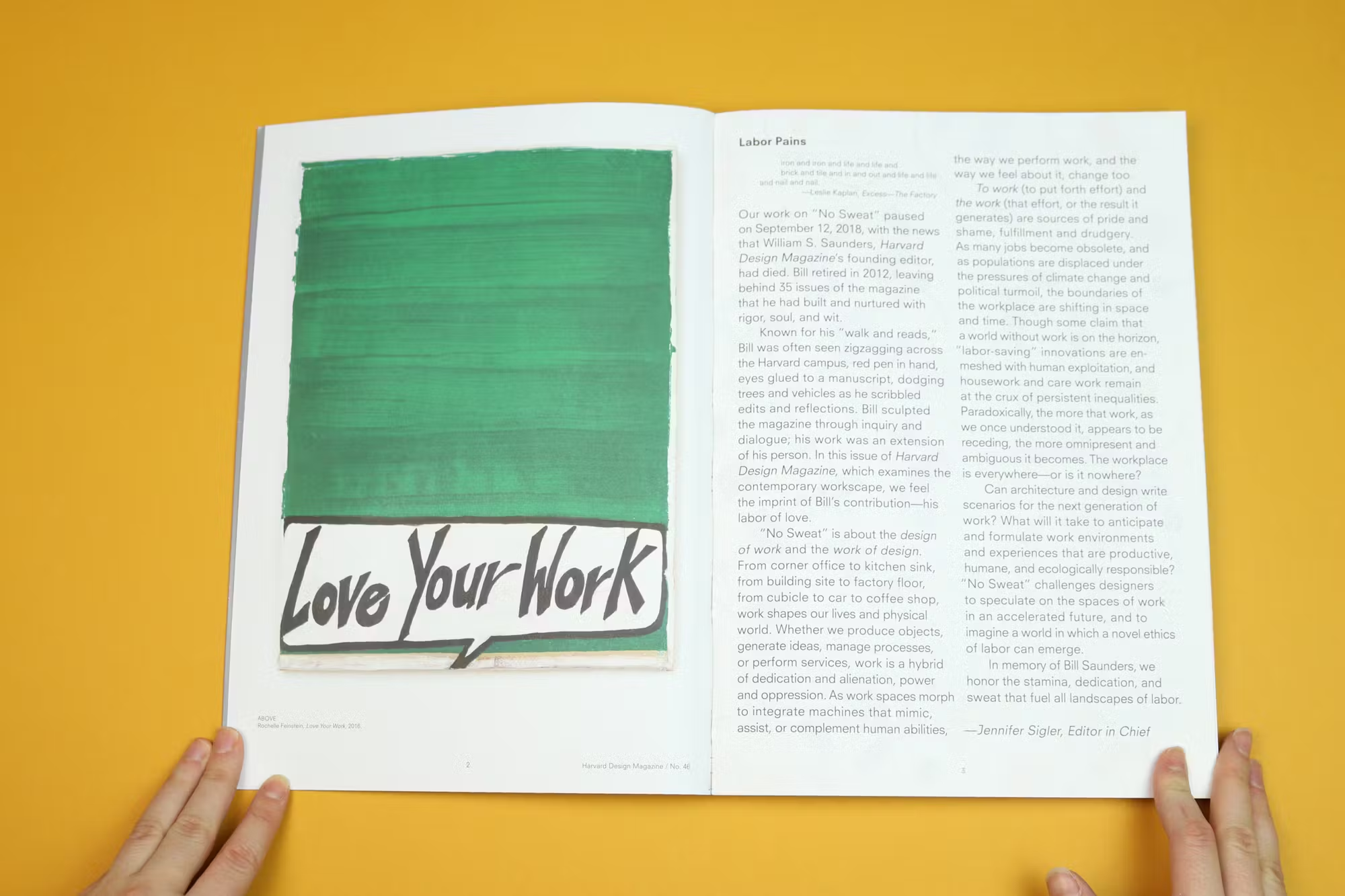

Love your work?

There’s a weirdly provocative illustration next to the editor’s letter in this issue of Harvard Design Magazine. It reads “Love Your Work”. Set in a speech bubble against a jaunty dark green background, it feels, uncomfortably, like an order. Looking at it, you’re made guiltily aware that you probably don’t love it. Should you? What we do, in our workaholic culture, is bound up with who we are. Hating, or even merely liking your job is not enough. Not loving it feels like a personal failure.

That conflict, between labour as “pride and shame, fulfillment and drudgery”, as editor in chief Jennifer Sigler puts it, is picked out within this work-themed issue. Wryly titled ‘No Sweat’, what’s inside is surprising: like the essay by an architect who tells us they are so out of love with work they were only able to bring themselves to write this after taking 20 milligrams of Adderall. Or the piece tracing the disappearance of the porn-set as workplace, as performers transform their dinners, gym visits and toilet trips into social media marketing opportunities.

Design, to the uninitiated, can feel like something abstract or technical — unconnected to the political or the day-to-day. Published by Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, HDM shows us how it defines the ways we work and live. From office tampon bins, to tackling climate change, this issue’s stated aim is to use design to “imagine a world in which a novel ethics of labour can emerge.” A considered, challenging read, ‘No Sweat’ feels vital.

We asked the editors about work as power and oppression, and whether we have a right to be lazy.

Past issues have been themed around subjects such as oceans and fear. This time, you’ve focused on work. Why?

Labour is evergreen as a topic, but today there is particular urgency to critically consider it given a number of pressures, including climate change, changing labour markets, the rapid development of AI and digital technologies, and migration. Labour has increasingly come to the fore of design discourse, and we felt that certain perspectives could be gathered in the magazine in a provocative way. We wanted to reflect on the evolving landscape of labour, but also to look at how our own discipline — the work of design — is changing.

When we decided to make the current issue, we felt that it would be valuable to look at work and labour directly, rather than sidelong through other themes. Everyone is touched by issues of labor — as workers and as inhabitants of a world in which we all depend on the labour of others. We have a responsibility to acknowledge labourers and the work that keeps us alive, keeps our cities functioning and healthy (or not), keeps our governments working (or not), and keeps us connected (or alienated) as a species.

The issue picks out the double-edged nature of “work” — the fact that it is both “power and oppression”. Was that fact — that most of us don’t love our work — part of what motivated you to theme an issue around it?

Love Your Work (1999) is a fresco by the artist Rochelle Feinstein. The piece and the pairing with the editor’s note can be read in many ways, and the ambiguity is part of the tension we sought to build. The phrase “love your work” appears in a speech bubble, implying an emptiness of language — the imperative of the phrase loses its force and becomes a near platitude or cliché. We are often told, especially in so-called creative industries, that we should, in fact, love our work — and many of us do! But the assumption that work should be pleasurable — love inducing — is problematic when so much of labour is menial, underpaid, and exploitative; this of course is particularly true in the art and design fields. But given that work is what we do with most of our time, we all, in some ways, aim to find pleasure in it. It’s a tension that cannot be resolved. But we ask in the editor’s note that readers consider “imagin[ing] a world in which a novel ethics of labor can emerge.” With that, loving work might be more feasible.

In one of our favourite pieces in the issue, the design of one contemporary boarding house in Korea is used to illustrate, among other things, that the whole concept of the nuclear family is a cultural construct. Does design usually play such a startlingly direct role in creating and cementing our social norms?

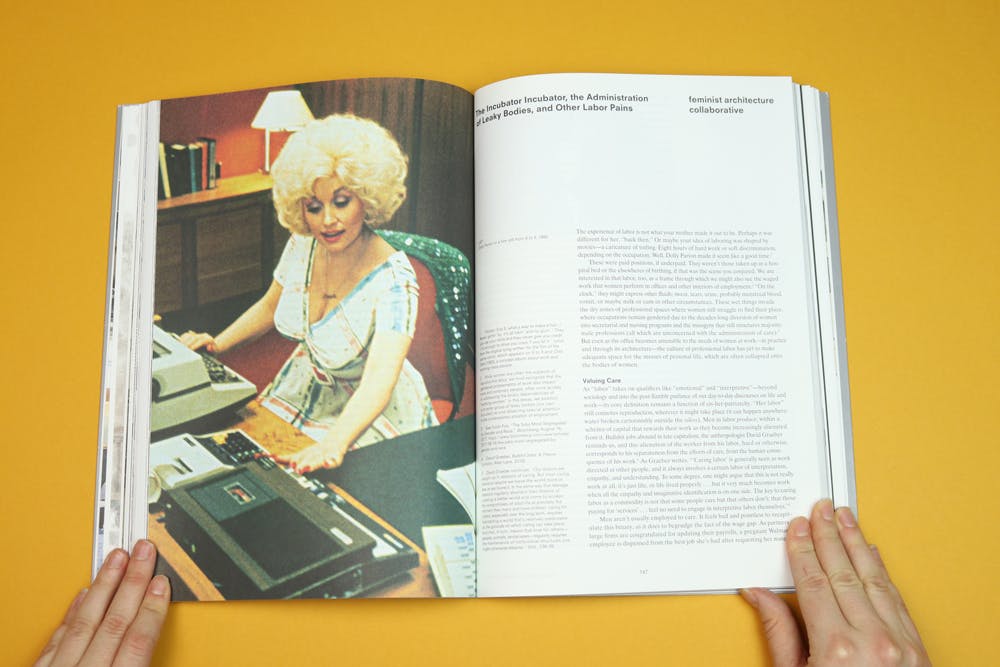

Design defines our lives in many ways, on numerous scales. Maria Shéhérazade Giudici’s essay that you mention, “Alone like the Horn of a Rhino: Reproduction, Affective Labor, and the Contemporary Boarding House in South Korea,” is premised on the conceit that the spatial planning of a house, and very particular typologies of houses in South Korea, have defined familial relations and social expectations for generations. Maria’s piece also echoes many of the ideas explored in our 2015 issue on family, “Family Planning.” The reality that design permeates and determines how we work and live is made evident throughout the current issue — and all other issues as well. For example, “The Incubator Incubator, the Administration of Leaky Bodies, and Other Labor Pains” by a feminist architecture collaborative unveils how offices, office design, and office culture have historically been conceived of by cis white men, whose needs and bodily realities differ quite distinctly from women workers and their bodies. They write:

“The new mom is one figure whose needs we’ve agreed to tolerate, and, as a consequence, she is less desirable as an employee. But for the rest of the leaky workforce, shall we institute pods for crying? For sweating? Free bleeding? These activities are relegated to bathrooms that may or may not be outfitted to accommodate such expulsions. Places to dispose of your spent tampons, to dump out your menstrual cup (not in a stall situation!), to inject your hormones, to apply concealer over the cyst you nervously picked at, to rub Tiger Balm on your shoulder knot, to mop your brow, to attend to all the unsightly measures of caring for your own body that might make you appear less capable of doing the job you were hired for. We spend time suppressing these habits in a culture of work where errant bodily conditions can be disqualifying. And so we put a partition between them and our computer screens.”

Elsewhere in the issue, Benedict Clouette’s conversation with the anthropologist David Graeber, “Pretending to Work,” elucidates how “bullshit jobs” are nurtured in work spaces like the cubical. And in Irene Figueroa-Ortiz’s interview of the pioneering civil and farmworker rights activist Dolores Huerta, the two discuss migrant farmworker housing and conditions of climate change as contexts that can be remedied by design. The ways in which we work and live, and thus our relationships to those things, are made manifest through micro and macro design decisions — as banal as the space between two desks to the accommodation of precarious, disempowered workers.

“What do we do with the poop?” was one of the most memorable questions in the issue. How would you sum up the connection between work and climate change?

“What do we do with the poop?” was asked by artist and writer Diann Bauer in her piece, “Crisis of Work.” She makes important connections between labour, climate change, and planning practices. One thing among many that we can learn from her piece is that we must build cities that can be resilient, adaptive, and responsive to the realities of climate change — and that process takes a huge amount of human labor. Climate change is going to influence our lives and the physical infrastructure of our cities and rural environments in ways that aren’t prepared for, which in turn will introduce the need for new kinds of work—new jobs in new sectors. The need for building cities holistically — understanding them as part of a larger ecosystem, one that is radically changing, and changing often in inhumane and inequitable ways — must be addressed through the mental and physical labour that will allow us to continue to live hospitably on this planet.

It feels like there is an emphasis in the issue on the ways we are exploited by the idea we are lucky and grateful to be working. On happiness as a justification for oppression. Do we have a right to be lazy?

We definitely have a right to be lazy! That phrase, made famous by Paul Lafargue (Karl Marx’s son-in-law) in his essay of 1883, sounds as revolutionary today as it did a century and a half ago. Many pieces in the issue, including Adjustment Agency’s “Refusal after Refusal” — or Jonathan Olivares’s “The Business of Pleasure at the Berrics,” which explores the pleasure of work in skateboard culture, among others — question how we might, through design, be able to reclaim our relations to labour, be it through refusal or connecting over shared interests. Much work today is underpaid and exploitative, and we believe that design can and should take initiatives for ameliorating such circumstances, cultures, and realities. Niklas Maak, for example, investigates the realities of post-work futures in his essay “Worlds without Work: From Homo Ludens to UBI Urbanism” — thinking through play, collective living and working, refusal, and automated realities that may lead to initiatives like universal basic income. There are many (design) solutions out there!