The obscure French artist credited with changing public attitudes to AIDS

Theming an entire issue around one esoteric French artist is an almost obstinately uncommercial thing to do. The editors of Tinted Window, whose first edition is devoted entirely to writer and photographer Hervé Guibert (1955-1991), say they acted out of obsessive love. “Those who really read him don’t admire the work,” editors Alex Bennett and Oscar Gaynor explain, “they crush on it; crush on him.”

Dedicated to intimate detail, Hervé Guibert wrote of his artistic purpose, “to tell the absolute truth, that was all I had ever done”. Credited with playing a considerable role in changing French public attitudes to AIDS, from the time of his diagnosis in 1988, Guibert set out to record his life and dissect it. His most groundbreaking novel, To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life (1991), describes lovers and companions close to him — including the dying philosopher Michel Foucault — devastated by the disease in Paris. Recurring themes in his writing and photography are compassion, companionship and transiency. His body of work, as the editors so beautifully put it, “can be read as a collection of un-dead moments and relationships”.

Tinted Window gathers new translations of Guibert’s writing, as well as stories and essays inspired by his work. The latter are long-form, tender and inward-looking; a testament to an artist who was confessional. Towards the end of the magazine, one contributor, Bruce Hainley, writes about how he started reading Guibert when a close friend killed himself. Hainley describes, with a painful vividness, the experience of seeing his friend in one of Guibert’s characters, suddenly and very clearly: “I was […] pulled into that strange intercourse there is between experience and writing — and reading.” It’s this awareness of the way a writer or a text can cut into and colour your life that makes Tinted Window significant.

The editors agreed to give us a five-point guide to the issue, and their passionate love affair with Guibert.

Just the one

“Our first issue focuses squarely on the writer and photographer Hervé Guibert. It does seem wilfully uncommercial on the face of it. But we were certain the writing and artwork would have the power to affect a lot of people, such was its intensity, and the novelty of encountering it in the English for the first time. There’s a head of steam building on the importance of Guibert and his work, as well as a resurgence of interest in the AIDS activism in which Guibert played a role — especially with groups like Gran Fury, Act Up and General Idea. The feeling for him is so intense and his work feels wholly idiosyncratic, in particular as a proponent of ‘auto-fiction’, something that is more and more relevant to contemporary fiction. This, coupled with the fact that the catalogue of his work is relatively unknown outside of France, made it a simple decision.

For us, as two writers whose work can feel curtained off from the ‘real world’, publishing is ultimately some kind of political gesture. It’s pushing your tastes on a group of people and saying, ‘we really think you should get into this’. We wanted to make a publication that acted as a salve. There’s a multiplicity of perspectives on any given subject — this issue is tinged with melancholy and adoration — and it seems like a worthwhile job to put those two feelings together, especially at a time when narratives can feel so singular.”

Smitten with Guibert

“We have both come to Guibert properly via the fanaticism of those that have written about him. Those that really read him don’t admire the work, they crush on it; crush on him. His mode of address transmits kinship. After a frenetic burst of emails, we connected with other smitten lovers; writers and artists who almost demanded that we pool all this so far uncollected energy together.

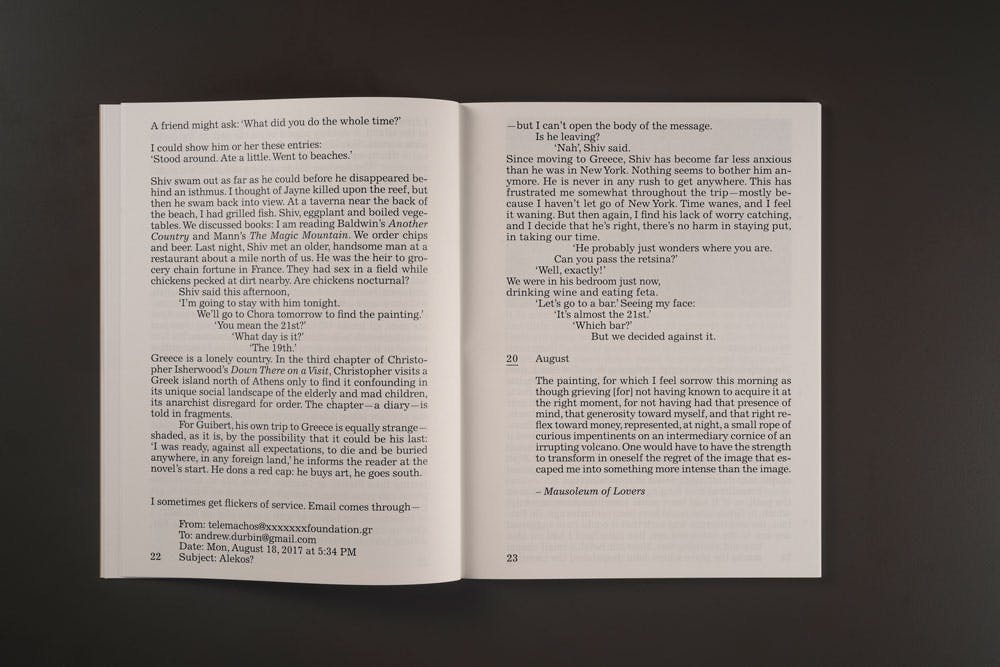

In a way, I think this obsession, or feeling of living in Guibert’s world is typified by Andrew Durbin’s short story Skyland, in which he travels from New York to Greece in search of a mythical painting of Guibert mentioned in his novel The Man in the Red Hat. For us, Guibert’s book Ghost Image hit our sweet spot: a transposition of a theory of photography on top of tracts of memoir.

Coming to subjects in this way is exciting for us – producing a publication that is really equal parts magazine, journal and fanzine. Tinted Window can act like a lightning rod for pockets of little-spoken thought, geography and biography.”

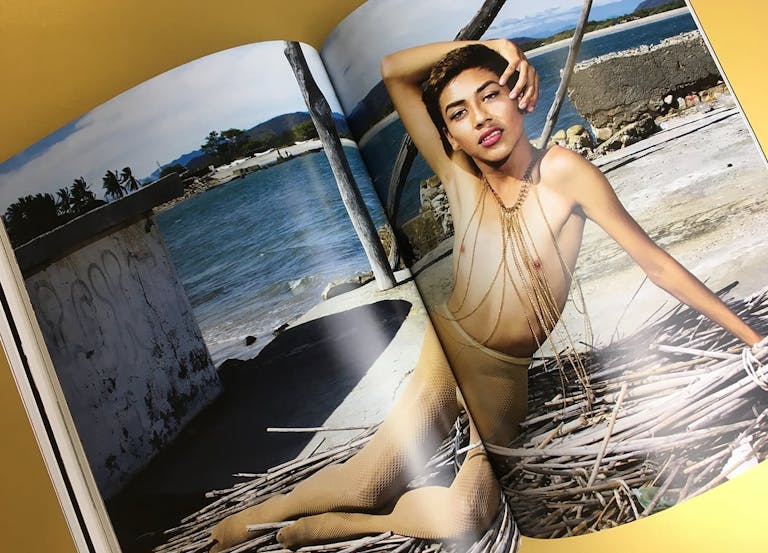

Eroticism

“John Douglas Millar, in his essay for the issue, locates a particular kind of eroticism in Guibert’s photographs: his ‘imagination resonated between the poles of fleshly putrescence and the clarity of a monastic cell’. Sunlight sweeping across a barren room insinuates touch, as does the fumbled and amateurish photograph of a lover’s naked body. In Guibert’s words, the image itself is a sort of illicit intimacy; photography is:

‘[a] second truth or lie which will produce itself, but something will appear, something will reveal itself, something will betray itself… I will imprison it, and it will be like evidence. The secret of the other shall be my secret. And this face which stares at me can very well decompose: it is already dead.’

In his only video work, La Pudeur ou L‘impudeur, there’s a charge, too, when he films the face of his grandmother; she on her deathbed and he in the late stages of his illness. With the square-on close-up of her face — pallid and worn by the chemical/physical reckonings of old age — he interrogates both their imminent deaths. She is obviously close to death, he is perhaps not so close, asking ‘what do you fear of death?’, ‘what do you love in life?’ When he presses her on this, there’s eroticism in what truth skin can possess, and the intimacy of a shared fate. In this way, a catalogue of his photographs is a bit like a dictionary of an erotic lexicon; some determinedly randy and moist, but many that explicate rarer and less popularly used formations. Guibert died several months later in 1991 of AIDS-related causes.”

Ghosts/Shadows

“Guibert was someone who was interested in transiency and the preservation of moments, certainly. But there are as many instances of full-throttled and carnal reckoning in his work. He encapsulates a sense of melancholy and loss as well as the throbbing vein of the present tense.

Guibert was little-known as either a writer or photographer in his life — up until the publication in 1990 of the novel, To The Friend Who Did Not Save My Life. Around this time, Guibert appears on the French TV talk-show Apostrophes, and talks candidly about AIDS as well as the character of Muzil in the book. Muzil is the pseudonym for the philosopher Michel Foucault, and the friend of the title. Foucault’s ‘outing’ caused a stir in French intellectual life, but Guibert says that he had always been (potentially we’re slightly misquoting here) ‘what we call a closet queen’. Guibert is evidently ill — daily life, as we see in his film, is shown as a sort of bureaucracy of health regimes and medicine-taking and doctor’s visits — and so are many of his friends. But in this confrontation with the media he is this sort of electric eel, weaving eloquently and poignantly through staid assumptions.”

Concrete poetry

“One way of manhandling the obscure into a more general context is through appealing design. Our designers, Regular Practice, share our attention to text and typography. We wanted clarity and concision; making the letter form a feature can take it from word to pictogram. Concrete and visual poetry is something we’ve been invested in for a long time. Our Tinted Window type comes from a weird bit of mail art ephemera we found caught in the dust flap of another book: a paper fortune teller game made by Dom Sylvester Houédard.

The content for our second issue comes out of all of this. The focus next time will be on an exhibition from Venice in 1978, ‘materializzazione del linguaggio’, a collection of visual poetry, sound art and performance made by eighty-two female artists. We actually found the catalogue for it in the same pile as that dust flap. Like with the Guibert issue, we’re continuing to commission new translations into English — this time with original English translations of the amazing catalogue texts.”