Mo makes really great eggs

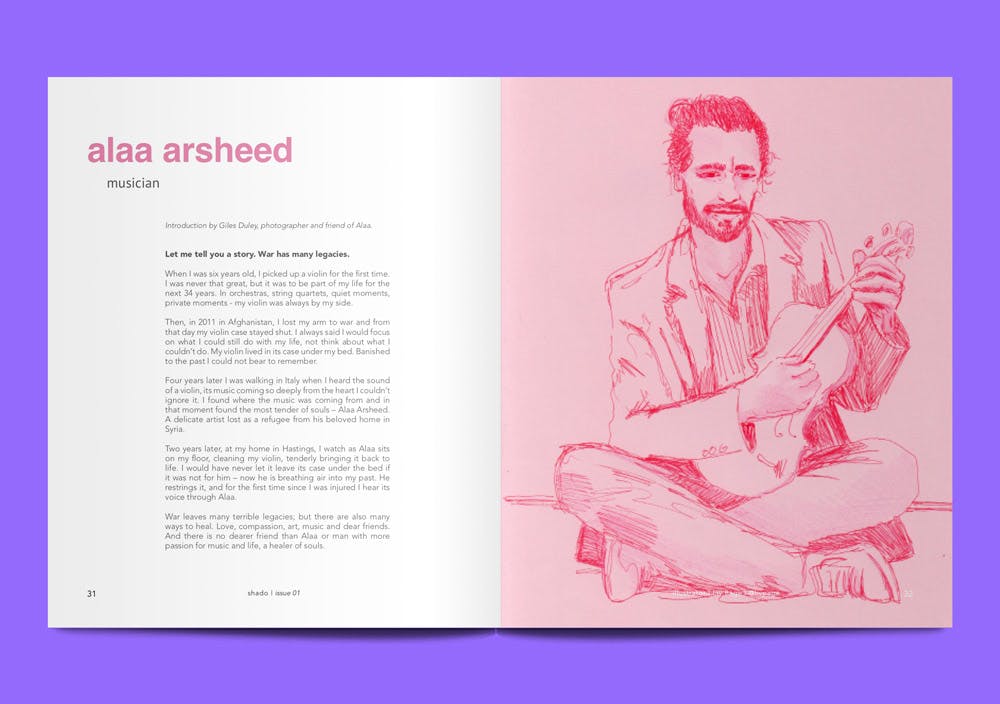

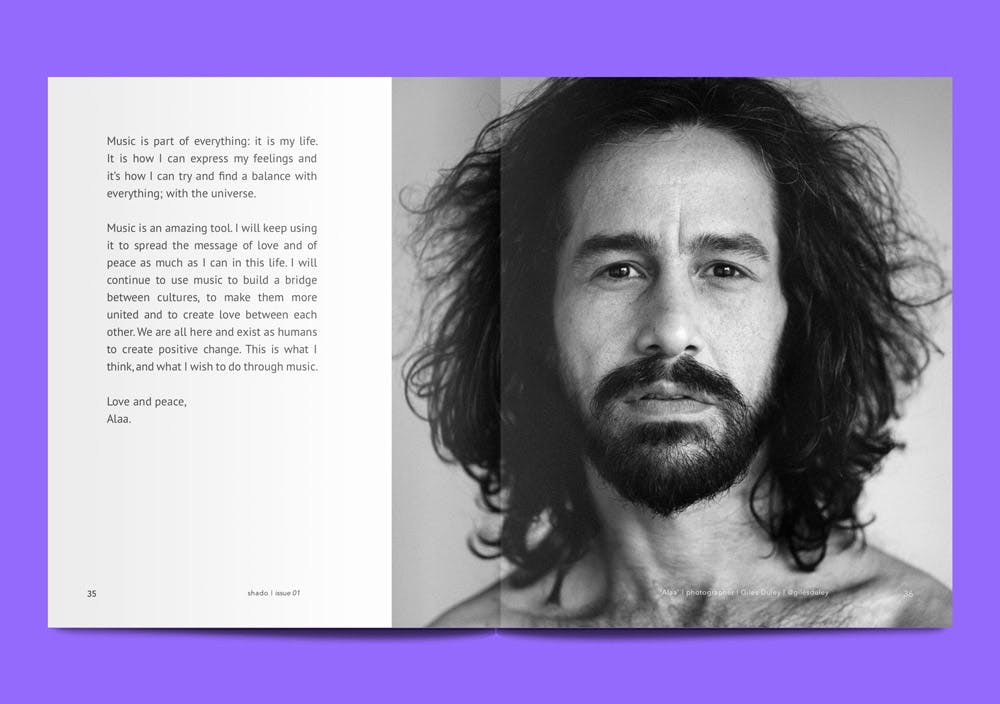

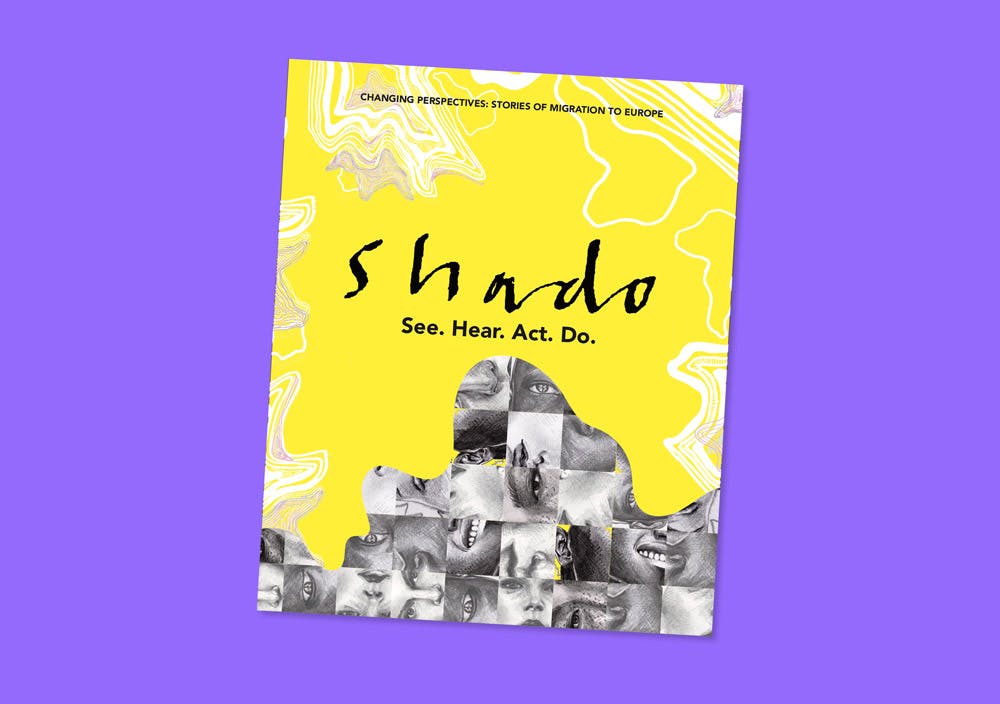

Shado is a collective trying to make space for people to tell their own stories. Issue one focuses on migration, and 70% of its contributors have refugee or asylum-seeking status. The priority, as editors Hannah Robathan and Isabella Pearce explain, “was moving away from the stereotypical, singular narrative of migration”. With a focus on the arts as a form of advocacy, on these pages, you will find makers and thinkers whose work both responds to and transcends their circumstances. Like chef Mohammed Rahemah, who invented his signature take on shakshouka over a tiny gas stove in the Calais Jungle, and now hosts Mo’s Eggs, a monthly pop-up brunch in London. Or Iranian visual artist Majid Adin, who just created the official video for Elton John’s Rocket Man.

The editors talked us through their motivations, plus a few favourite pieces in the issue.

A photographer you feature in the issue, Abdulazez Dukhan, writes that he wanted to represent aspects of life in a refugee camp that weren’t being shown by the media. Most strikingly, the smiles. Was that struggle for a different kind of representation part of what motivated you to make Shado?

Completely. The rhetoric around migration in this country and in Europe as a whole — the EU aren’t exempt from this — has created a completely hostile conversation. In short, the act of migration has been criminalised: rather than looking at the reasons why people are forced to flee, we focus on the numbers; instead of standing by EU and global policies of human rights, governments have been pouring money into border control and ignoring (read: passively supporting) the police brutality which is absolutely rife in places like Northern France, the Balkans and Greece. This, in turn, exacerbates violent and hateful responses from the general public.

Specifically in Abdulazez’s case, he was reacting to the methods of European photojournalists, who would hang around the camp where he lived, just waiting for a fight to break out. They would snap the photo and sell it to tabloids to fuel anti-refugee rhetoric, adding to the scaremongering tactics employed by so many European leaders. Abdulazez took up photography — self-taught — to show the everyday, human perspective from residents of the camps. Their smiles are part of daily life; a reminder of humanity which gets lost in the deliberately criminalising photographs taken by so many photojournalists.

Your contributors write about themselves as people first, not migrants. I’m thinking about the chef Mohammed Rahemah here, and the writer Arif Abdullah Haidary. With the former, you’re writing about really great eggs — rather than the horror of the migration crisis. Was that a deliberate decision?

Well, this is precisely it. There is a huge issue with dehumanisation and also tokenisation of those who are experiencing, or have been through, migration. Everyone who is included in Shado is there because of the strength of their work. ‘Migrant’/’Refugee’ is not a nationality or an identity. It is a circumstance. Shado contributors may have experienced migration, but that is not their label. Mo is a chef; he is not a ‘refugee chef.’ His experience isn’t something that defines him — he is a chef who makes incredible eggs! Similarly, Arif is a skilled writer, and was a journalist back home in Afghanistan. He is not a ‘refugee writer.’ While some of our contributors do talk about their experience of migration, that is their own prerogative. If they believe migration to have shaped their current arts practices, they talk about it — but it’s not for us, the curators, to place labels on them.

The Iranian visual artist Majid Adin is profiled, who made the official video for Elton John’s Rocket Man. It’s beautiful. Can you tell us about him, and how that video came about?

Majid is brilliant. He was actually forced to flee his home after he created a political cartoon which criticised religious conservatism in Iran. Facing persecution, he made for Europe, and arrived in London via Calais in 2016.

In 2017, Elton John created an international competition for the creation of official music videos for three of his most iconic songs. Majid won with his animation for Rocket Man, the iconic ‘70s hit. His video draws on some of his own experiences of migration to Europe. The animation, now a viral YouTube video, parallels the experience of the astronaut going to Mars with a man leaving his home to find safe refuge in London. The video speaks to viewers on a basic, human level. It’s evocative and moving. That is the strength of art as a global language: it allows you to make connections with situations you may never have experienced yourself.

One article calls for a psychosocial understanding of the UK asylum system. Can you explain what that means and what it might look like?

That piece, contributed by Hannah Joy, talks about a situation which is very invisibilised: the 4 stages of PTSD experienced by those forced to flee their homes due to conflict and persecution. There exists a general assumption that the arrival to the UK or another stable country is the endpoint to someone’s trauma. In actual fact, it can sometimes mark the beginning, and it is often precisely at this moment that any mental health impacts are exacerbated. Upon arrival, as well as reconciling personal emotions and accessing painful memories, those seeking asylum are hit with the reality of the stark lack of integration and inclusion facilities in host countries — which obviously have a knock-on effect on ideas of personal belonging and identity. Elsewhere in the issue, Pilo Moreno writes about his firsthand experience of the mental health repercussions of living in indefinite detention in the UK.