Mold Magazine wants you to care about the future of food

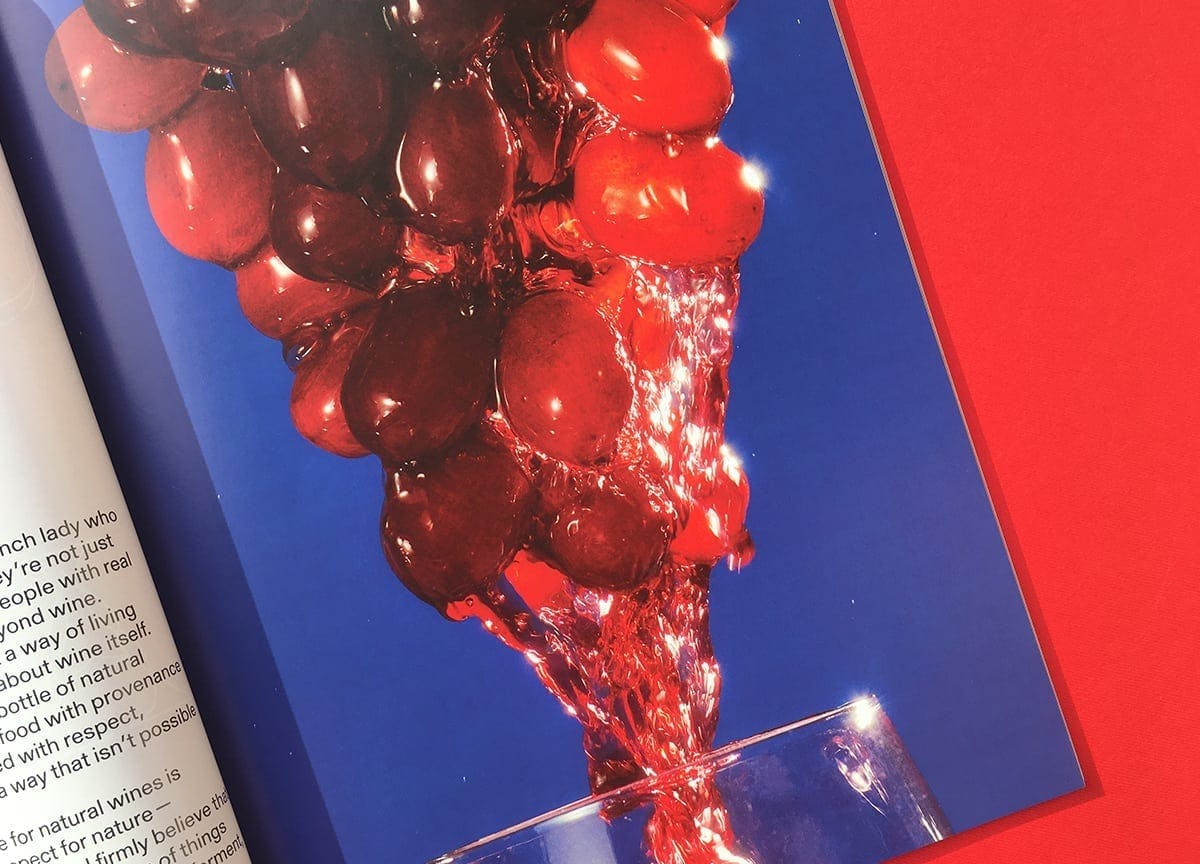

From recipe blogs to food magazines, it is rare today to come across an image of food that doesn’t entice you to indulge. But for LinYee Yuan and Johnny Drain, the monopoly of highly-stylised ‘foodie culture’ in the media can be problematic. They think that this fetishisation of the things we eat does little to curb an imminent food crisis, so their new project, Mold Magazine, wants to highlight the way design can offer solutions and affect positive change.

Mold is the latest magazine to join the Stack lineup, so we took the chance to speak to them about bidet toilets, cow innards, and the future of food…

Mold Magazine started in 2013 as an online platform discussing the future of food. Why was it time to put it into print?

LinYee: Print offers a unique form of storytelling that invites an audience to consider text, art and materiality in a beautiful, compact format. I had already been publishing stories online for three years that explored the boundaries of food design, and the responsibility that designers might have in offering solutions to the coming food crisis. Still, it didn’t feel like a clear call to action around the possibilities for design to be an agent of change.

So the impetus behind Mold Magazine was to create an opportunity where we could do an in-depth exploration around a single idea. Print has a way of finding its audience in a more organic, and sometimes more personal way. We wanted people to sit with the idea that they might be able to affect change in a really specific way and be inspired by the work that others are doing to create a more sustainable and resilient food system.

Why do you feel like it’s important to offer a counter narrative to over-stylised ‘foodie’ culture?

Johnny: There’s a lot of serious problems with how the world feeds itself at the moment — few but powerful agricultural stakeholders, prevalence of monocultures, water supplies, inefficient use of resources, skewed distribution of the food we’ve grown, quality/disparity of diets and malnutrition — it sounds dry, but it’s so important. Much of Western food culture, despite its powerful voice and influence, doesn’t seem remotely concerned with those problems. We want to be part of the conversations that are focusing on how, in 5 or 50 or 150 years time, we can have made changes to ensure more people have diets that help them live well, without obliterating great swathes of the planet and its oceans.

I particularly enjoyed the article on Toto, the manufacturers of bidet toilets where designers wear ‘empathy suits’ to do their work. Why did you want to tell that story?

LinYee: I’ve been obsessed with Toto toilets since I first came across one in the back of a ramen restaurant in New York City. Toilets, as a whole, are rarely celebrated in the pages of beautiful magazines even though they are objects that we have some of our most intimate relationships with — we interface with toilets multiple times a day, often touching them with our bare skin. I wanted to write a story that really examined their potential as design objects and collaborators. The idea that toilets of the future might perform a sort of alchemy by telling us a more complete story about our health through examining what we call ‘human waste,’ is quite wonderful.

The Digestive Car is a fascinating idea — tell us about the thinking behind that feature, and some other highlights for you in issue one.

Johnny: This project from YiWen Tseng, which imagines how cow innards and their impressive ability to produce methane from grass might be reengineered to produce methane to power automobiles, is probably my favourite. There’s this wonderful dichotomy of them being gross and disgust-inducing, yet beautiful and intriguing. They look like they smell repulsive but you feel you want to move towards them, touch them, smell them; or at least I do!

I really like the yoghurt feature too, where we brought together perspectives and stories connected to yoghurt from around the world. It’s such an unshowy food but there’s incredible richness, diversity, innovation — and all these key elements that characterise the human experience: love, sex, childhood, family, religion, science, politics — stitched into its history and use. That’s true of all foods really, you just have to dig a little sometimes, which is what we’re trying to do to some extent when we say we’re interested in getting away from the shallowness of the current ‘foodie’ culture.

Lastly, could you tell us about your team?

LinYee: I started writing about industrial design in 2010 and fell in love with designers and their process, not to mention their unique way at interpreting the world around us through the built environment. Designers are trained to ask the right questions, research topics by consulting experts across various fields, and propose human-centered solutions. These skills are going to be critical for thinking about how we might address the coming food crisis.

Johnny: I did a PhD in Materials Science but have since been working on more hands-on food projects and research. For example, I researched whether the aging of butter can be controlled to make something palatable, like an aged cheese — as opposed to just rancid — at the Nordic Food Lab, and helped some ramen shops in Switzerland make the ‘perfect’ noodle.

—

We love magazines — Sign up to Stack and we’ll deliver our favourites to your door each month