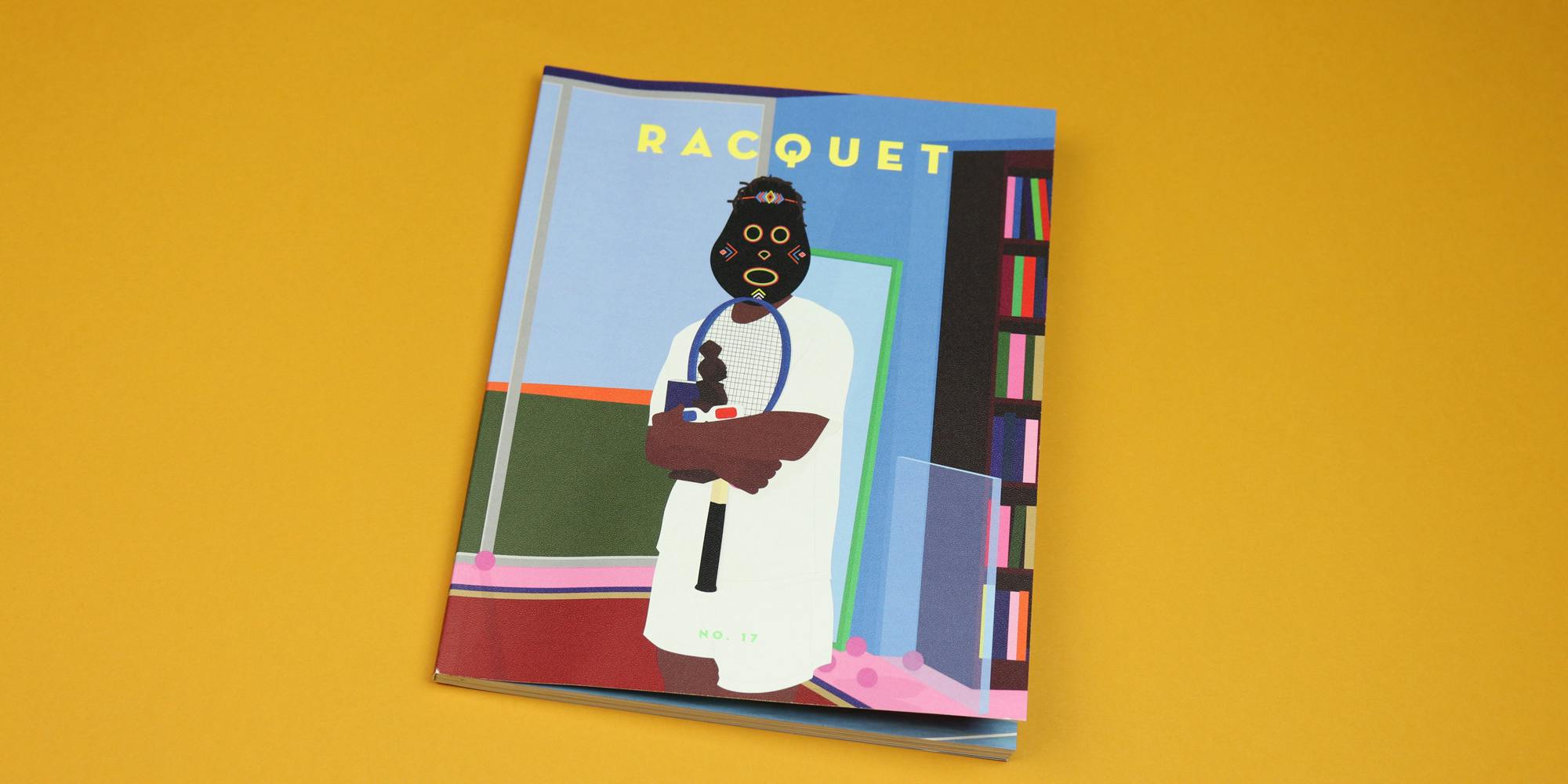

Naomi Osaka guest edits Racquet magazine

The 17th issue of quarterly tennis magazine Racquet is guest-edited by world no.1 Naomi Osaka. Released late in August 2021, the issue has added poignancy now, read in the light of Osaka’s decision to take an indefinite break from the sport following her shock US Open exit just days later on September 3. Osaka explained her decision in terms of a falling out of love with the game, which she said made her miserable when she lost, and strangely joyless when she won: “I feel like for me, recently, when I win I don’t feel happy. I feel more like a relief. And then, when I lose, I feel very sad. I don’t think that’s normal.”

Anyone who has ever played the game can relate to this feeling. Tennis is lonely, and it attracts exceptionally driven people, perhaps more so than any other sport. In an Instagram post from August, Osaka was open about the fact that the underside of the kind of single-mindedness it takes to play tennis at this level is self-hate: “Internally I never think I’m good enough […] I’ve never told myself I’ve done a good job but I do know I constantly tell myself that I suck or I could do better.”

Osaka’s opening letter for Racquet, written weeks or perhaps months before her exit from the US Open, hints at her disaffection, but the magazine itself tells a different story. The work Osaka has commissioned for the issue — including a series of photographs of amateur Haitian players, and a fascinating essay about the unexpected prominence of tennis in Japanese manga — is a testament to love of the sport. It is this conflict, between love and hate, that animates the issue (and perhaps most players).

Below, we’ve picked out a few of the most suggestive pieces.

In the first essay in the magazine, the writer Kenji Hall reflects on how Osaka, who plays for Japan, has changed the discourse around race in the country. Osaka’s appearance at the US open, where she wore a face mask bearing the name of a different victim of racial violence to each of her tennis matches, is seen as a turning point for Japan. Osaka’s protest was harshly criticised in the Japanese media, where racism is rarely addressed, but she persuaded other Japanese athletes to fight against racism, as well as drawing attention to discriminatory stop-and-search practices in the country.

Fashion and culture journalist Jessica Iredale writes about how Naomi Osaka’s personal style, which Osaka herself describes as “too wild for America and too tame for Japan”. The piece is illustrated by Nike sketches of Naomi’s US Open looks, as well as high-fashion designs by Mari Osaka, Naomi’s sister and collaborator.

In what is perhaps the most fascinating piece in this very fascinating issue, writer Matt Alt does a deep-dive into the world of sports manga: from blockbuster manga comic book The Prince of Tennis, which has sold more than 51 million copies worldwide; to a relatively new comic, Unrivaled Naomi Tenka-Uchi (which translates to ‘Naomi, Unrivalled Under The Sun’). Alt’s essay is rich and detailed, providing a brief history of tennis in Japan, as well as an analysis of why the country is home to a demographic of obsessive adult consumers.

Osaka was born to a Haitian father and a Japanese mother, and this issue of Racquet is in many ways an exploration of that heritage. For the central photo-series in the magazine, Osaka commissioned FotoKonbit, a nonprofit organisation which supports Haitian photographers, to document the country’s blossoming tennis culture. Caught in motion, the players serve skilfully, but with palpable joy. From this commission, more than any other, it is tempting (although perhaps rather presumptuous) to infer that Osaka loves her sport, and the people who play it.