Gods, monsters, and Foucault on self-care

Dotted with winged eyeballs and an ancient, disembodied head, the third issue of This Is Badland turns inward to examine “the cult of the self”. Exploring art and culture in the Balkans, the inspiration was the skyline of Tirana, Albania, where monuments to communist leaders in the public squares have been replaced by glistening steel towers. “Estranged from shared belief systems,” the editor’s letter explains, “we joyously and monstrously morph into each other’s idols”.

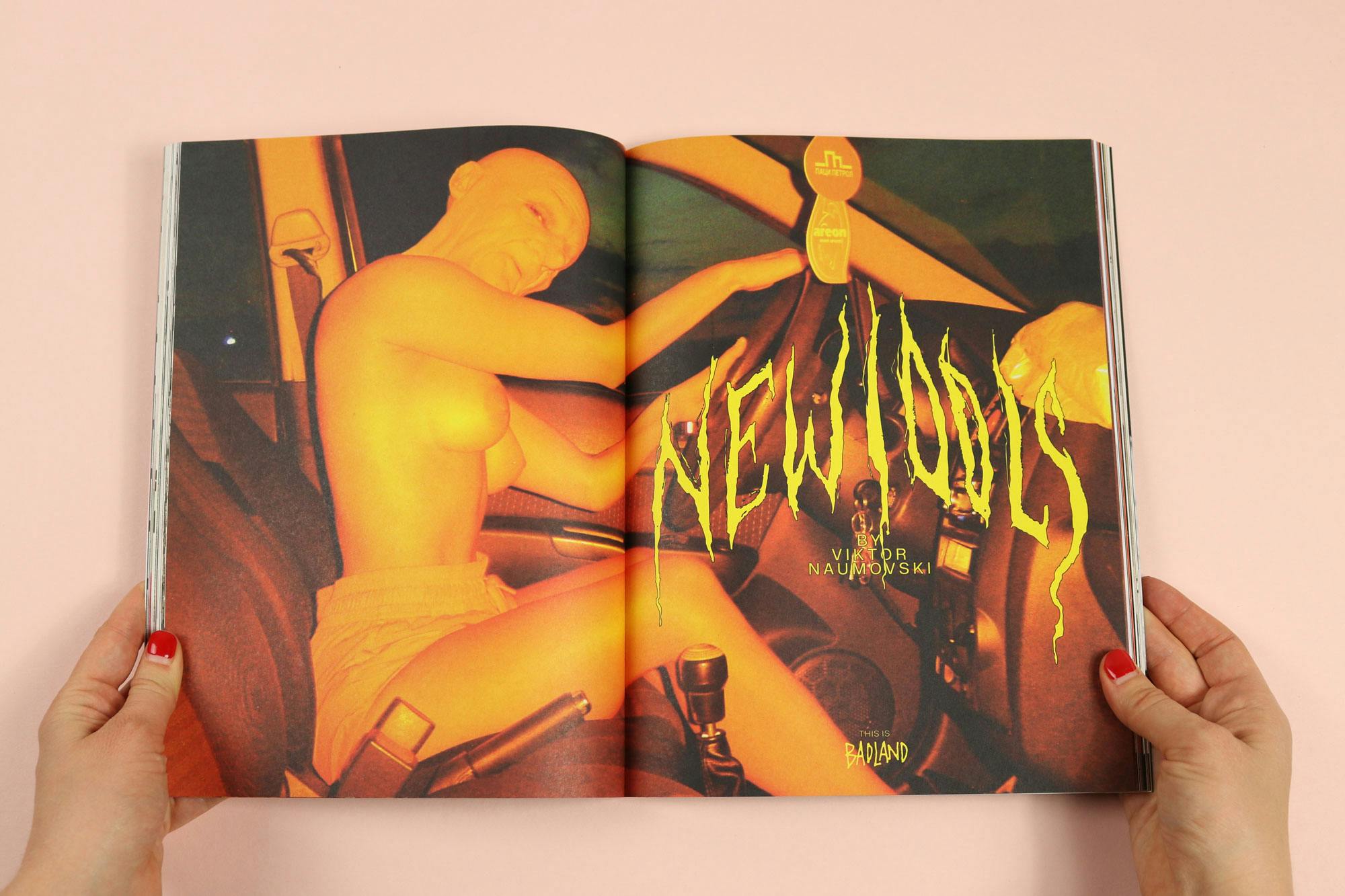

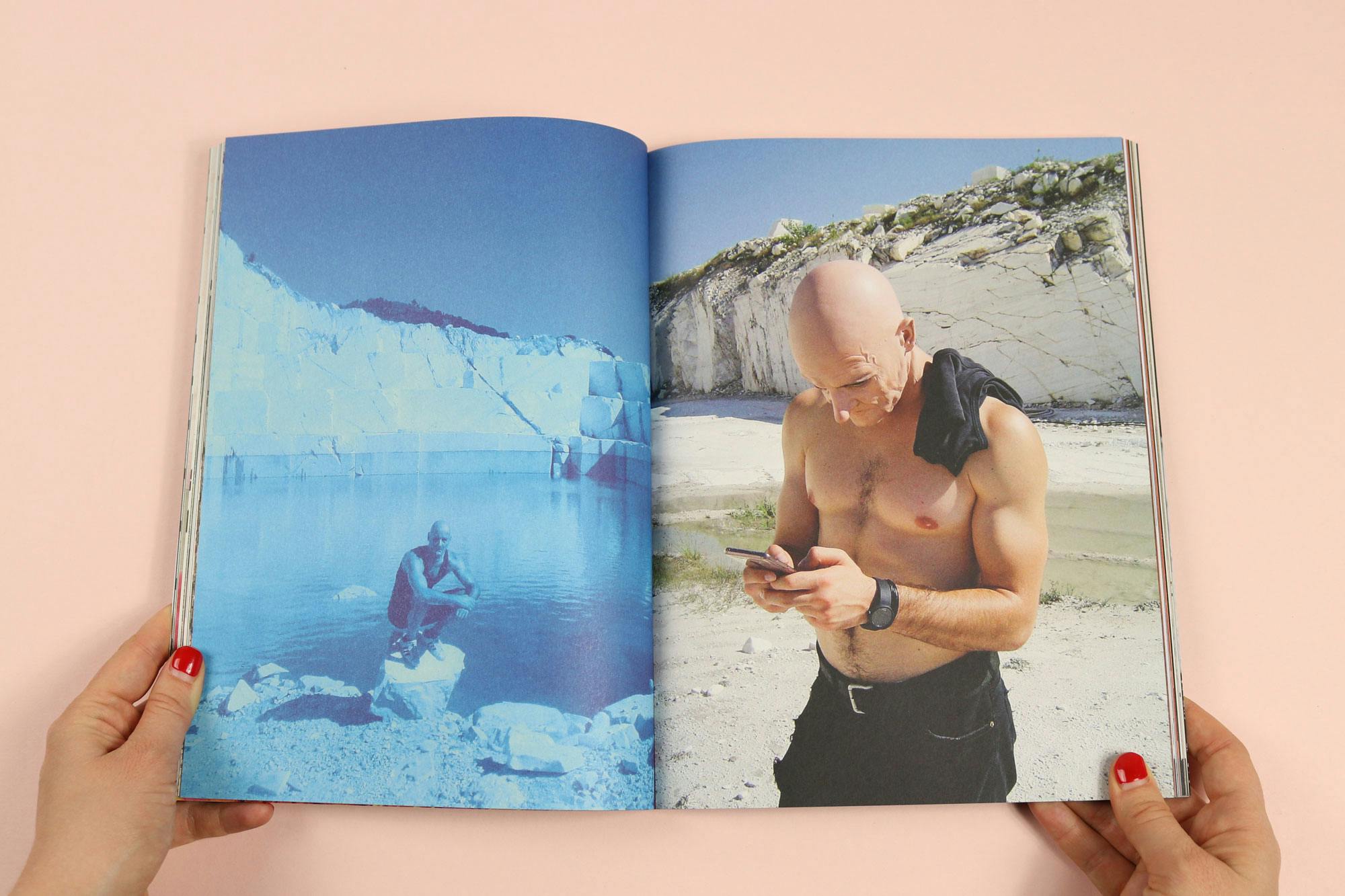

Much of the work here is monstrous – in a thrilling way. In one extraordinary photo essay, the artist Viktor Naumovski takes a road trip around Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, Macedonia and Serbia with a 3D replica of his grandfather’s head on the front seat. A piece about new face bending app ‘Narcisse’ is accompanied by images of eery, mirrored masks that cling to the features like a shroud.

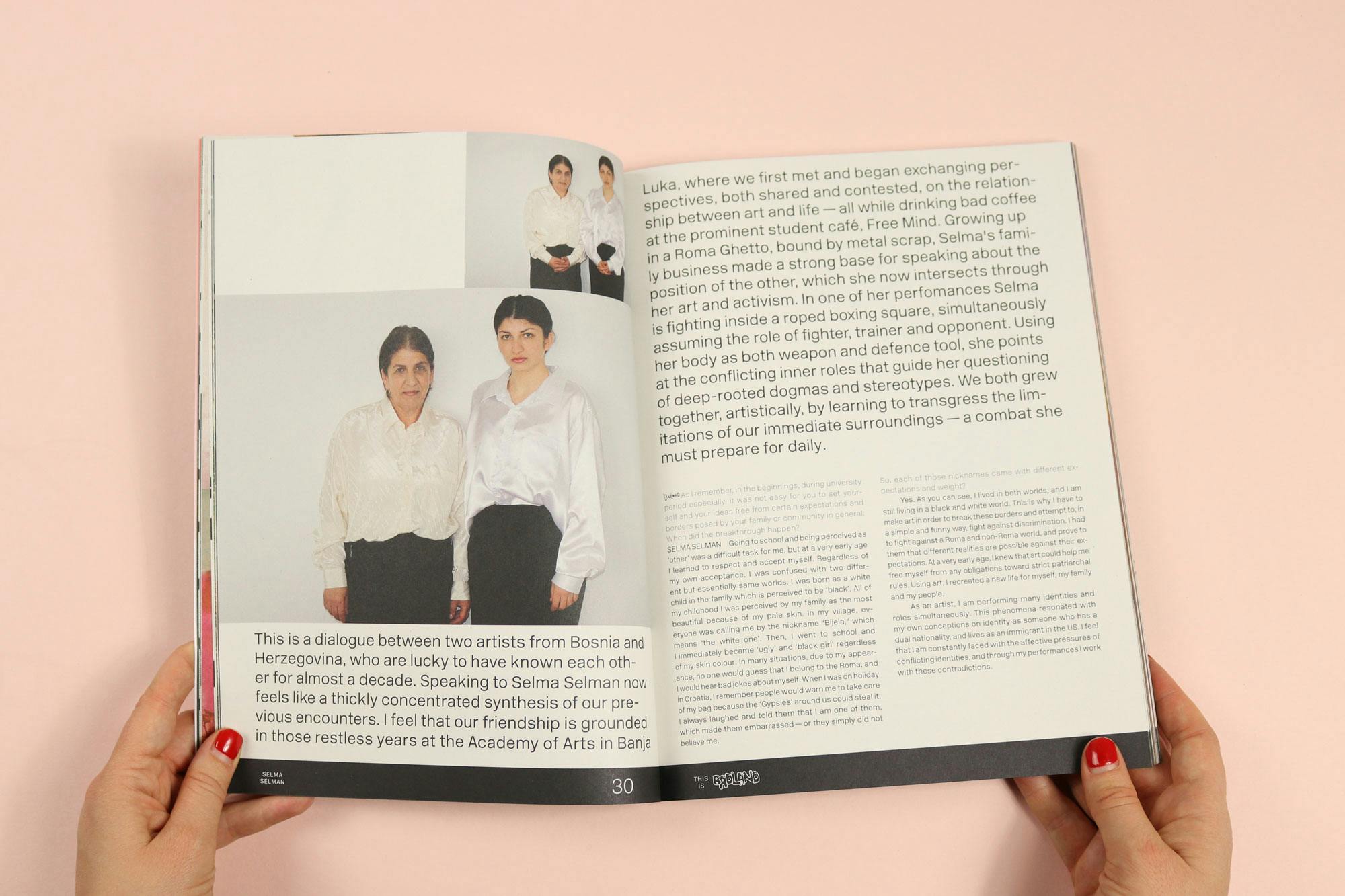

What makes Badland so remarkable, though, is the rigour with which it interrogates self-worship, and the old gods who came before. Academic to the point of being occasionally a bit baffling, this is not a relaxing read. One of our favourite pieces in the issue profiles Croatian healer Braco, tracing the idea of self-care through Foucault and back to Hellenistic times, where examination of the self was already a status symbol practised specifically by those in a position to govern others. In another fascinating interview, the Bosnian artist Selma Selman talks about her series on unrealised dreams, and the story of her mother’s child-marriage that inspired it.

Editors Rafaela Kaćunić and Nina Vukelić talked us through the new issue.

Many of the images in this issue feature distorted, post-human aesthetics. Most obviously in the feature about facial augmentation technology ‘Narcisse’. Are you drawing a connection between post-human aesthetics and post-communism?

Visually, we would render this issue into a mirror, but one with a rippled surface reminiscent of a water — collapsing, destabilising and retracting reality in unexpected ways. Our story “Narcisse” sees Johanna Jaskowska engaging with this on a meta-level by subverting the standards of Instagram beauty. In much of the imagery throughout the magazine, we probe into the libidinal economy of looking and being looked at. By questioning the notion of gaze, which has a strong presence in this issue, we sought to redefine the relationship between aesthetics and politics.

There’s an interesting focus on the ‘new’ throughout the magazine. You begin with a piece about the significance of the ‘pre’. Why is the ‘pre’ important to this issue?

One of the main conceptual forces behind this issue came from visiting Tirana and witnessing the rapid accelerations in the socio-urban environment there. It was fascinating because one could experience powerful transformations on a very material, baseline level. Reflective high-rise towers have replaced the bygone monuments to communist leaders (Tito, Stalin, Mao Zedong) that once occupied public squares (you can find those today decaying behind the National Museum). So yes, through this issue we set out to weave an intricate web of associations around the complexity and urgency of our present and future times.

We live in disorienting times, marked on one side by the loss of belief in the myths of neoliberal “monuments”, and infant-stage alternatives on the other. Yet rather than reaffirming the bleak scenario of twilight time and unstable future, we wanted to open up this issue to different perspectives. By reconsidering modernity as a primitive and “pre” formation we sought to engage with the necessity of starting all over again.

The artist Selma Selman’s work about her mother’s child marriage and consequent struggle to obtain citizenship is striking. Selman talks about how the work has become “a functional method used by many to obtain citizenship denied by a collective historical trauma”. Could you explain a little about her motivations?

Her art has to do with innovation; with finding new ways to look at things; with being relentless about not accepting the same formulas and conventions. Selman sees her work as an art-based toolbox to heal internal, inter-personal and collective traumas. Her approach to art is grounded in creating situations that expand possibilities for personal, collective and cultural growth, and resist oppressive processes.

How far would you say This Is Badland as a whole is informed by “collective historical trauma”?

Collective trauma is of course part of a larger narrative in the background of topics we are dealing with. It is also a loaded and tired trope in terms of framing someone’s work. We try to go beyond the fetishistic representation to bridge together individual poetics and social reality.

The shoot with the horrifying masked face of Viktor Naumovski’s grandfather is amazing. Can you explain a little about the story behind that series?

Viktor is a prodigious young photographer with whom we strongly resonated. We worked closely on bringing to life his ‘New Idols’ visual journey — which follows him and his friends in the remapping of the route his grandfather took across different countries in the Balkans. Viktor’s upbringing in the suburbs of Skopje aesthetically and conceptually shapes this feature. Viktor used a fictional narrative to explore the intersections of identity, family relationships and heritage.The growing sense of tension permeating the story is rooted in the ambiguous idea of hybrid idols, and shaped by his experiences in diaspora, and his love for the transgressive and the absurd.