Stop making sense

Yuca isn’t an easy read. That’s a compliment: it’s not trying to be. Referring to themselves as “partners in crime”, Colombia-based editors Juliana Gómez and Lina Rincón have transformed magazine-making into something deliciously illicit: a covert creative act you need to find some kind of excuse for, because it operates outside the bounds of polite, productive society.

The theme for this third issue is ‘time’, but cutting across that motif is a second idea: ‘sound’. They refer to this second idea as their alibi – the thing that gives them a rational excuse for the thoroughly irrational act of making this magazine in the first place, and while the result is disorientating, it also makes for a refreshingly active reading experience. Pieces are offered up with little exposition or hand-holding. Like the series of photographs of Turkish landscapes by Douglas Mandry, scribbled over with his subjective recollections of the trip. Or the eery cluster of empty documents by Peruvian artist Andrea Canepa, meant to represent the 10 main forms that all people fill out throughout their lives: from birth certificate to death certificate.

Gradually, faint connecting threads emerge: this is a magazine about the millions of lives, and millions of (faulty) perceptions that make up our ‘reality’. There is no single theme to Yuca, just as there is no single right way to read it, or no single point to magazine-making. Your subjective experience of these pages is part of the creative process. As the editors explain, “there might be no certainties any longer but we’re fine with that because this allows us to open our minds and senses to the unknown.” That feels like a strangely comforting message for our uncertain times.

The editors talked us through Yuca’s relationship with its country of origin, Colombia, and the danger of a single story.

You don’t have a single theme for each issue. Instead you also add an alibi. Why is that?

It’s a luxury. There are so many things we want to write about, the themes are really just excuses. We always felt from the beginning as editors that we were partners in crime, because we were doing this weird thing that no one understood. And for a while it really did feel like we were having to excuse ourselves. Magazines aren’t a good business decision. We were talking about Yuca and people kept saying, “Why are you doing this?” “It makes no sense!” The amazing thing though, is that we’re getting away with the crime. All the alibis we’ve had over the course of the issues — gastronomy, roots, architecture, now space and time — have worked, because they allowed us to create a free space to make something. There are no constraints — that is the greatest pleasure of making Yuca — we can do what we want to do.

You write, in the editor’s letter, about embracing a lack of certainty. That feels liberating in a time when we are certain of so little.

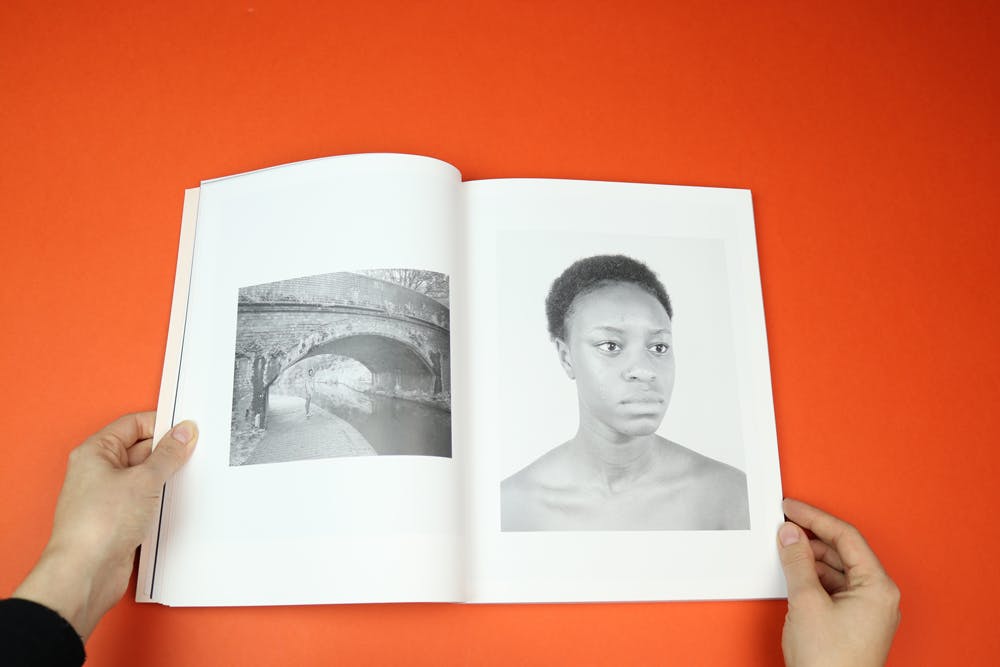

When things are fixed and thought out and organised and strict, there’s no room for possibility. If someone did a discourse analysis of the way we talk about Yuca, they would find that the word ‘possibility’ occurs like five times out of every 10 words. We don’t need to feel certain, because if we feel that we won’t believe in what’s possible. We don’t know what we’re talking about. Even if you think that’s what you think now, tomorrow it will change. We like to complicate our existing themes further when we open up to our contributors. We noticed that almost everyone we invited thought of sound in terms of silence, and time in terms of the past. So a secret third theme emerged: absence. That’s beautifully reflected in Edgar Martins’s opening images, which focus around the representation and imagination of an absent body, drawing on a series of families and individuals based in the Midlands, UK, as well as HMP Birmingham, its inmates and their relatives.

Your cover is a Make America Great Again hat on fire. Does your emphasis on uncertainty relate to political uncertainty?

If we are political, we want to turn away from any typical political narrative. We want to talk about synthesis: to relate politics to personal stories. We run a recurring feature called Beyond the Visible, where we focus on a country that is obscured by stereotypical or limited depictions in the media. As Colombians, we are very used to being seen in terms of generalisations. For our first issue we chose Israel and Palestine; then we looked at Colombia for issue two, at the time of the peace treaty; this time it was Iran. And we came from a place of ignorance: we knew of the romantic history of the country, the films and the poetry. And we knew what we read in the media. But in terms of human beings — their difficulties, and their joys — we knew nothing. As Colombians we really struggle with this: ours is the country of magical realism, or it is the country of violence. So we got in touch with contributors we knew in Iran and asked them what they thought should be discussed.

So as Colombians, you come from a place of frustration about the danger of a single narrative?

Colombia is so big and there are so many stories: it’s not just drug dealing, or flowers, or coffee. You will probably never find the way to tell the whole story of the place you belong. But the only honest way to approach it is to say: tell me your individual story. That representation of Colombia has been part of our lives, and it’s been something that makes us suffer, but it has also marked how we relate to people from other countries. A country is a collection of millions of personal experiences of life. It’s just people, like you and me. Just people struggling.

Being Colombian also gave us the idea that conflict is not always negative. In those places where things look the most fucked up, there is beauty. As extreme as the darkness is the light.

You quote Thoreau in the issue, “Most men lead lives of quiet desperation”. Can magazines save us from lives of quiet desperation?

Oh yes! At least they can invite you to move out of desperation. I think magazines have definitely saved us from living lives of quiet desperation! You shouldn’t stay still. You should challenge yourself to move. If Yuca can change just a little thing in one person’s mind — that’s enough for us.