The wartime magazine reaching new readers

A few weeks ago I published a blog post about reading the world’s first magazine, and the particular qualities that make it recognisable as an early form of the things we now call magazines. In the days afterwards I was contacted by a German designer, Thilo von Debschitz, who shared a link to curt-bloch.com, a project his design agency Q has been working on for the last 18 months, and which also reflects on the power of the magazine as a mode of publishing.

Curt Bloch was a Jewish lawyer who fled his home in Dortmund, Germany in 1933, escaping the Nazis and resettling in the Netherlands. But the Netherlands fell to the Nazis in 1940, and when mass deportations began in 1942, he went into hiding, joining an estimated 330,000 ‘Onderduikers’, or people in hiding from the German occupiers. It was dangerous and he made terrible sacrifices, including separating from his mother and sister, who were later arrested and transported to the Sobibor extermination camp, where they were murdered in 1943. But while he was in hiding he found an extraordinary way of coping with the fear, powerlessness and boredom that he must have experienced.

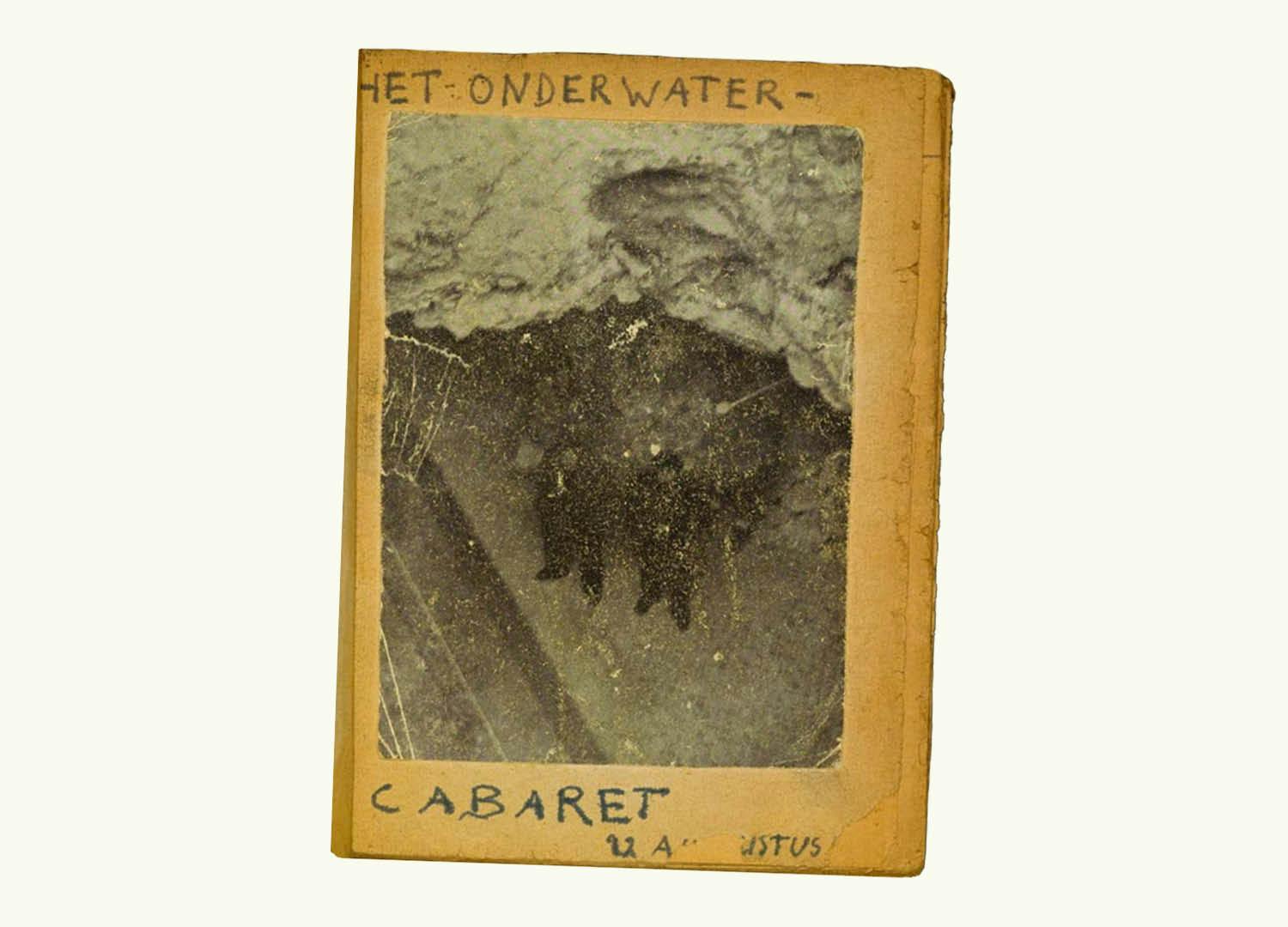

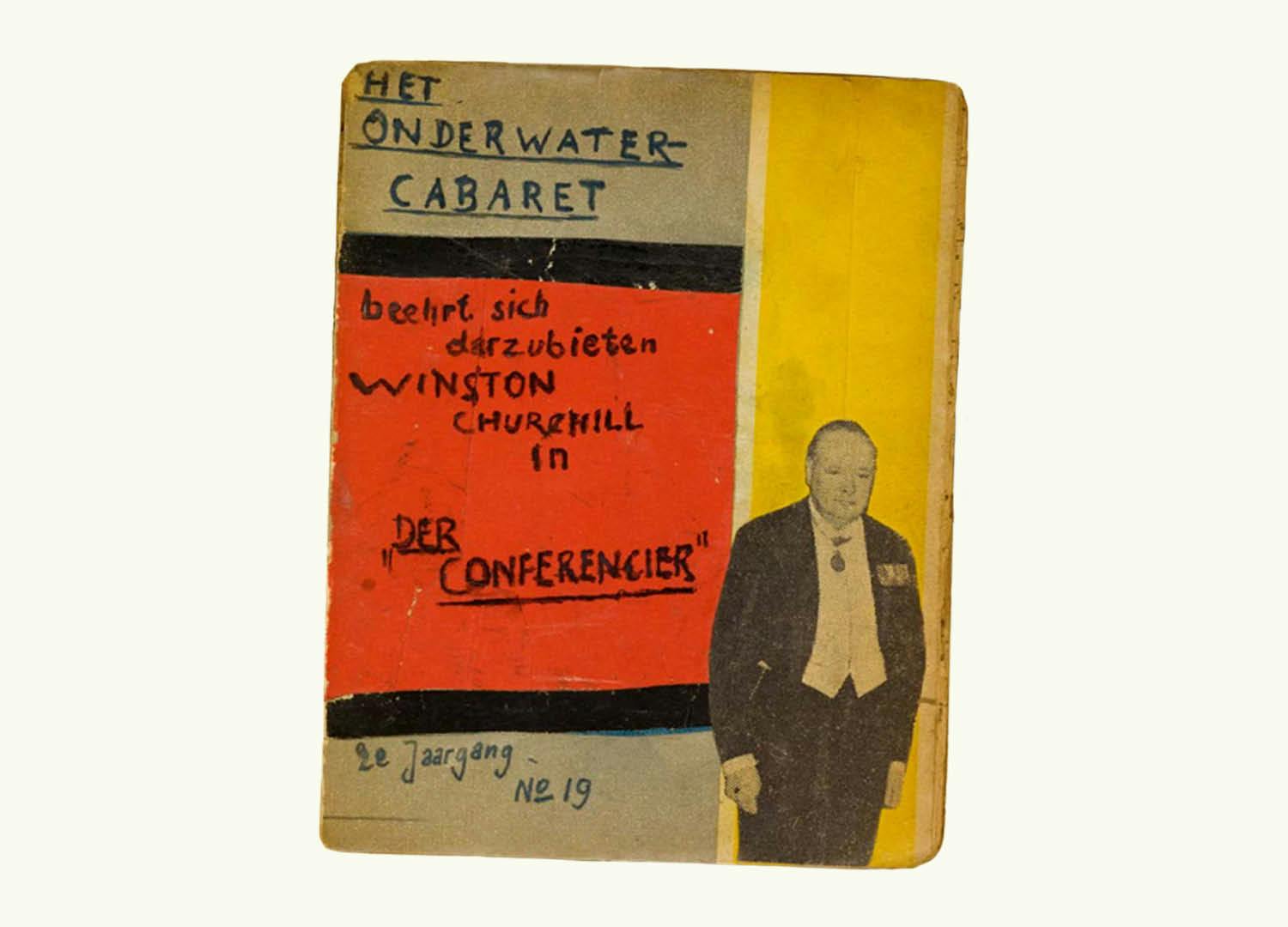

Beginning in August 1943, he published Het Onderwater Cabaret, a small, handmade poetry magazine written in Dutch and German, which commented on the course of the war, mocked Hitler and the Nazis, and reflected his emotional state as it swung between hope and despair. He produced just one copy of each issue, which was passed around the local resistance network to be read by other people in hiding and the individuals helping them, and over the course of the war he created an incredible 96 issues with a total of 492 poems across more than 1,700 pages.

I was amazed when I saw the magazine, with its beautiful and witty collaged covers that must have been created in the most hostile conditions by a man who had no previous experience as a designer. It seems clear that Het Onderwater Cabaret was being written for an audience, with its painstakingly crafted covers that were created to catch a reader’s eye, and its poems written in Dutch. (There are actually slightly more Dutch poems than German across the entire collection, and I find it remarkable that he was rhyming and punning in a language he’d only learned when he moved to The Netherlands a few years earlier.) I wanted to find out more about this extraordinary publication, so I arranged to speak with Thilo and also Simone Bloch, Curt’s daughter and the woman who first determined that her father’s magazine should reach a new audience.

Curt was liberated in 1945, and after the war he emigrated to New York with his new wife Ruth and their first child, Stephen, and after working menial jobs in local factories he set up a business importing antiques from Europe to the US. The magazines travelled with them and stayed on a shelf in the family’s lounge, and Simone says they didn’t play a huge part in her life growing up.

“My parents were antique dealers so my house was the opposite of minimal,” she explains. “I grew up speaking English and only learned to speak German after my father died when I was 15. He died suddenly and I was a rebellious teenager and we were not getting along so well… It was a long time ago, but it was a big deal.”

Faced with a collection of magazines written in languages that she didn’t speak, and freighted with feelings of guilt about her relationship with her father, she says she was aware of the magazines but didn’t spend a lot of time looking at them. Eventually, though, her own daughter became interested in the magazines, studying and transcribing some of the poems, and seeing them with fresh eyes made Simone feel that Het Onderwater Cabaret deserved a new readership. She had no idea how to go about finding those readers, though, and came up against several dead ends before she had a revelation: “Finally I thought, ‘My parents imported antiques from Europe. I need to export this to Europe.’ That was my epiphany.”

Invigorated by this new direction, she began searching for contacts in Europe and came across Thilo in a Facebook group for German Jews. Thilo didn’t reply straight away because he assumed he’d been approached by a bot or a scammer, but she persisted and once she had shown him the archive of magazines, he was hooked.

“I couldn’t believe that after 80 years this treasure is still around and nobody knows about it,” he enthuses. “I first looked at it as a graphic designer, considering the covers and these wonderful collages, which were very modern for the time, but then when I started to read the poems I was deeply moved. Because the fact it’s in rhyme makes it very easy for you to get the message and makes it a little bit easier for you to swallow the content, which of course is sometimes very sad. But it’s also funny, so reading it is a real rollercoaster ride. It knocked me out of my shoes.”

The magazines are on display at the Jewish Museum in Berlin until 26 May, but I’ve only seen them via curt-bloch.com, and of course that’s how the majority of people will encounter them. It can be difficult to communicate a physical magazine via a screen, but Thilo and his team have done a fantastic job of providing different entry points, for example allowing users to browse just the covers, or read Curt’s history, or follow a timeline of key events, or jump straight into the pages to see the handwritten poems and read them translated into German, Dutch and English.

When I spent time reading the world’s first magazine, I felt there was something about its humour and playfulness that made it stand out as definitely a magazine. That attempt to win a reader over and build a relationship across several issues has remained at the heart of what a magazine tries to do, and I think it’s evident in Het Onderwater Cabaret too. Some of the covers are openly humorous, while others echo the style of the wartime news weeklies like Picture Post, showing photography or illustrations depicting recent events. And likewise, whether he’s lampooning Hitler or reflecting on the fate of his mother and sister, there’s a sense that Curt is writing for his readers, as much as for his own entertainment.

From issue 33 of the second volume there’s also a major change, when he switches the name of the magazine to Het OWC, allowing for a stronger and more striking graphic style. I wonder whether the change was inspired by the fact that his readers had begun referring to the magazine as OWC? Or maybe he wanted to create the sense of familiarity and confidence that comes from the assumption that everyone knows what the acronym stands for?

It’s also striking that whereas most magazines settle into an established style as quickly as possible, Curt kept changing his cover layouts from issue to issue. Maybe that’s because he couldn’t rely on getting hold of the materials he needed each issue; maybe it’s because he wanted to keep himself entertained, and a new design each time was more fun than sticking to a template; or maybe, like a wartime Buffalo Zine or Viscose Journal, he wanted to communicate that he would keep on playing with his readers’ expectations and changing things up every time.

It’s impossible to know for sure what motivated him in his various hiding places, and how the magazine was received by its contemporary readers. But as the magazines finally reach a 21st-century readership, Thilo says he’s discovering a whole new meaning to the words on the page.

“Simone and I went to a school two weeks ago while she was still in Germany, and had students reading the poems, and it was a breathtaking experience. I think for Simone it was very moving, and for me it was proof that this should be taught in schools, because the rhymes are sometimes sort of like rap and it gets immediately into your brain. You learn a lot because there’s no topic that Curt Bloch wasn’t rhyming about, so there are battles in Japan, or the Russians are coming from the East, or the Allies coming from the West; and then there’s the way he mocks Hitler and Goebbels, or the way he is deeply concerned about his family. It gives a totally fascinating insight into his experience of the war, at a time when right wing extremists are on the rise again here in Germany and populism is growing everywhere.”

“My father was like Anne Frank meets Tupac with delusions of Stephen Colbert,” adds Simone. “The more I read the poems, the more I think that what he really wanted was to be a Goebbels for the left. All those poems he wrote in Dutch, I think he hoped he could get his propaganda into the world, but he knew he couldn’t. So that’s what we’re doing. And it’s not just propaganda; it’s a really strong, feisty voice.”

–

Explore Het Onderwater Cabaret at curt-bloch.com

Exhibition at the Jewish Museum Berlin runs until 26 May jmberlin.de/en/exhibition-het-onderwater-cabaret

Picture credit: Jewish Museum Berlin, Convolute/816, Curt Bloch collection, loaned by the Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of Curt Blochʼs family