Struggle and vulnerability in Kajet Journal

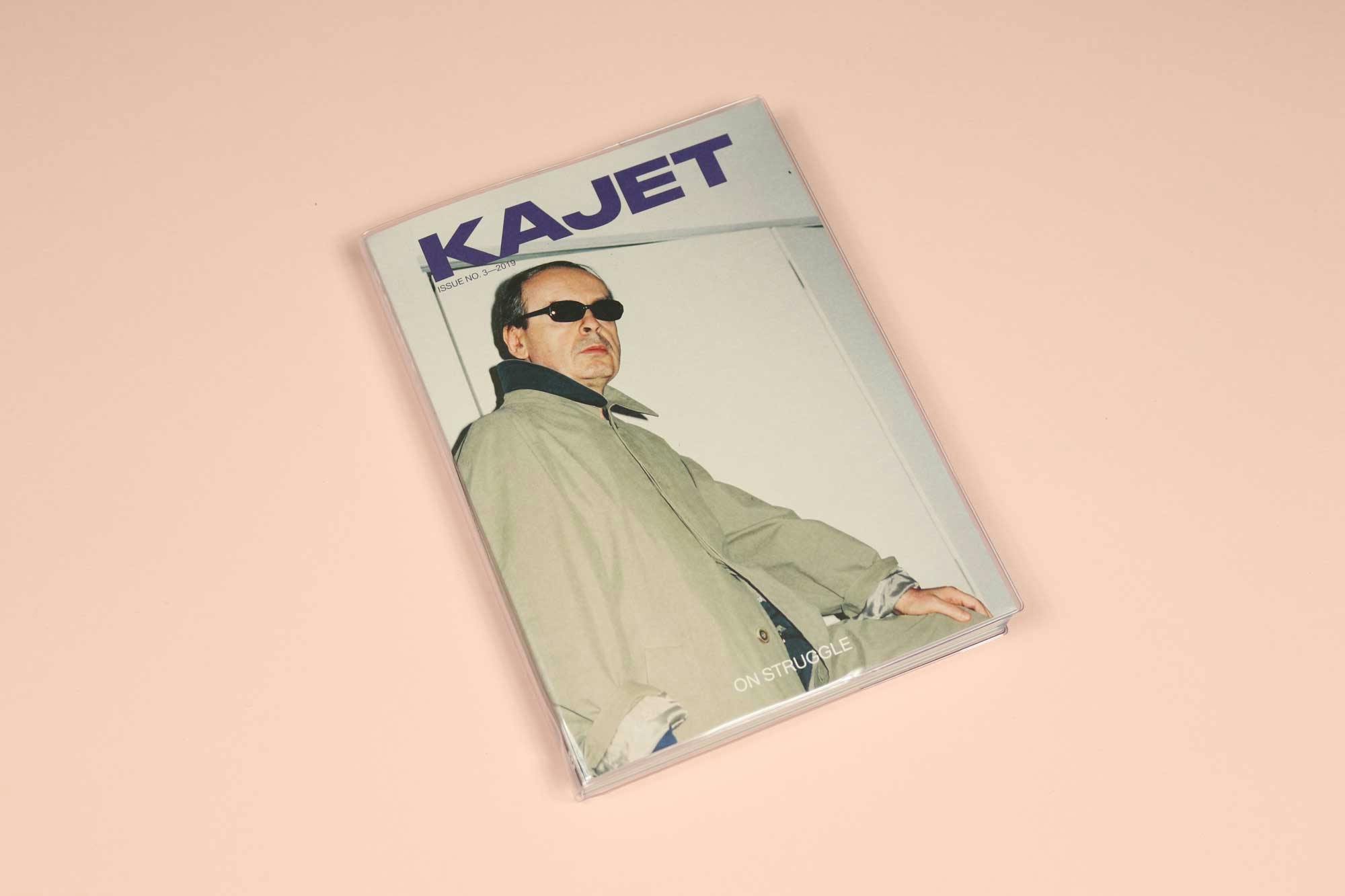

Back in April, we came across an unusually vulnerable tweet about how disheartening it can be trying to make an independent magazine. Kajet, a “journal of Eastern European encounters” was theming their third issue On Struggle. The process, they tweeted, had been fittingly bleak: while “print is indeed not dead… it’s a tough, grinding, uphill battle.” The resultant issue, published this summer, is a rich and sometimes difficult look at the way Eastern Europe is demonised by the West. The best pieces are intriguing in a similar way to that tweet, for their honesty. A photo story by Ramin Mazur about growing up in Transnistria asks, boldly, “Do other people feel at home here, or do they see it as a temporary place which they would swap for a more reliable one if they could?”

Out to prove Eastern Europe is “more than just itinerant gloom”, struggle is conceptualised on these pages as a wonderful thing, too: a way of dismantling oppression and refiguring the world. We caught up with “founding mother and father” Laura Naum and Petrică Mogoș to talk about the agony and the ecstacy of making a magazine.

Early on in the magazine, you print the suicide note of Soviet poet Mayakovsky: “The love boat has crashed against byt” ‘Byt’ is defined as the daily grind. Is that a struggle that particularly resonates with you?

Mayakovsky has a proto-existentialist take on the idea of struggle (his daily grind is less about personal, quotidian struggles, and more about a struggle toward revolution), but we’re thinking about byt in a contemporary context. Self-help literature encourages us to give up our daily jobs and follow our wildest dreams. Social media shows us countless examples of people who make it only after they try ‘hard enough’. But that has methodically proved not to be the whole truth. Our byt is not an exclusively Eastern European problem, as this lack of security is common to all territories marked by the global flows (and flaws?) of late-capitalism. Our byt is everyone’s byt. It is about precarious labour and anxiety, and the magazine is a product of that.

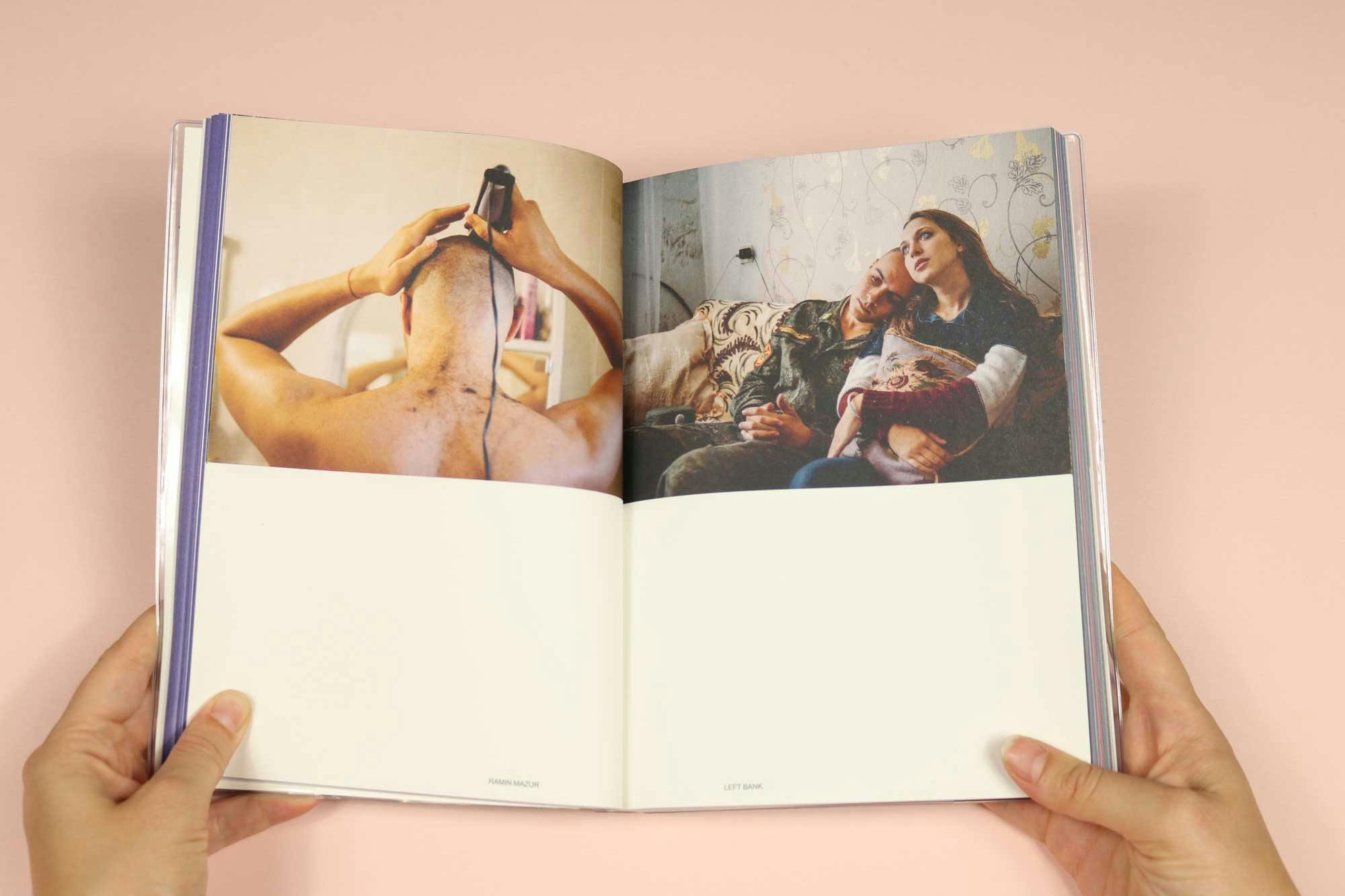

“Do other people feel at home here, or do they see it as a temporary place which they would swap for a more reliable one if they could?” This line, from Mazur’s introduction to ‘Left Bank’ is striking. Is this a question you struggle with personally? Or are trying to answer in the making of this issue?

Living in contemporary Eastern Europe seems to come along with a permanent sense of deracination, an alienating feeling of displacement and lack of belonging. We are constantly reminded that we are not good enough, that we need to change, to keep up the pace, to steady the ship before it’s too late. With such a constant discursive bombardment, a kind of artificial rootlessness can be easily internalised. In this way, Eastern Europe has come to be perceived — both by its inhabitants as well as its distant observers — as a space of inbetweenness, as a realm of impermanence.

In the opening feature, you talk about the “schizophrenic construction of Eastern Europe as the birthplace of evil”. Can you expand on that?

Eastern Europe remains for us a social, cultural, geographical, and — above all — political construct. Through a mythological process that started with the Enlightenment and was consolidated during the Cold War, Eastern Europe has been consistently represented as the Other. In this issue we make direct reference to instances of vilifying this Other and argue that Eastern Europe has been demonised by the West as having a certain monstrous history. We end up asking our readers: Is it really accidental that the most lasting Western mythological villains, from Frankenstein to Count Dracula, Nosferatu or the Golem, are connected somehow with Eastern Europe?

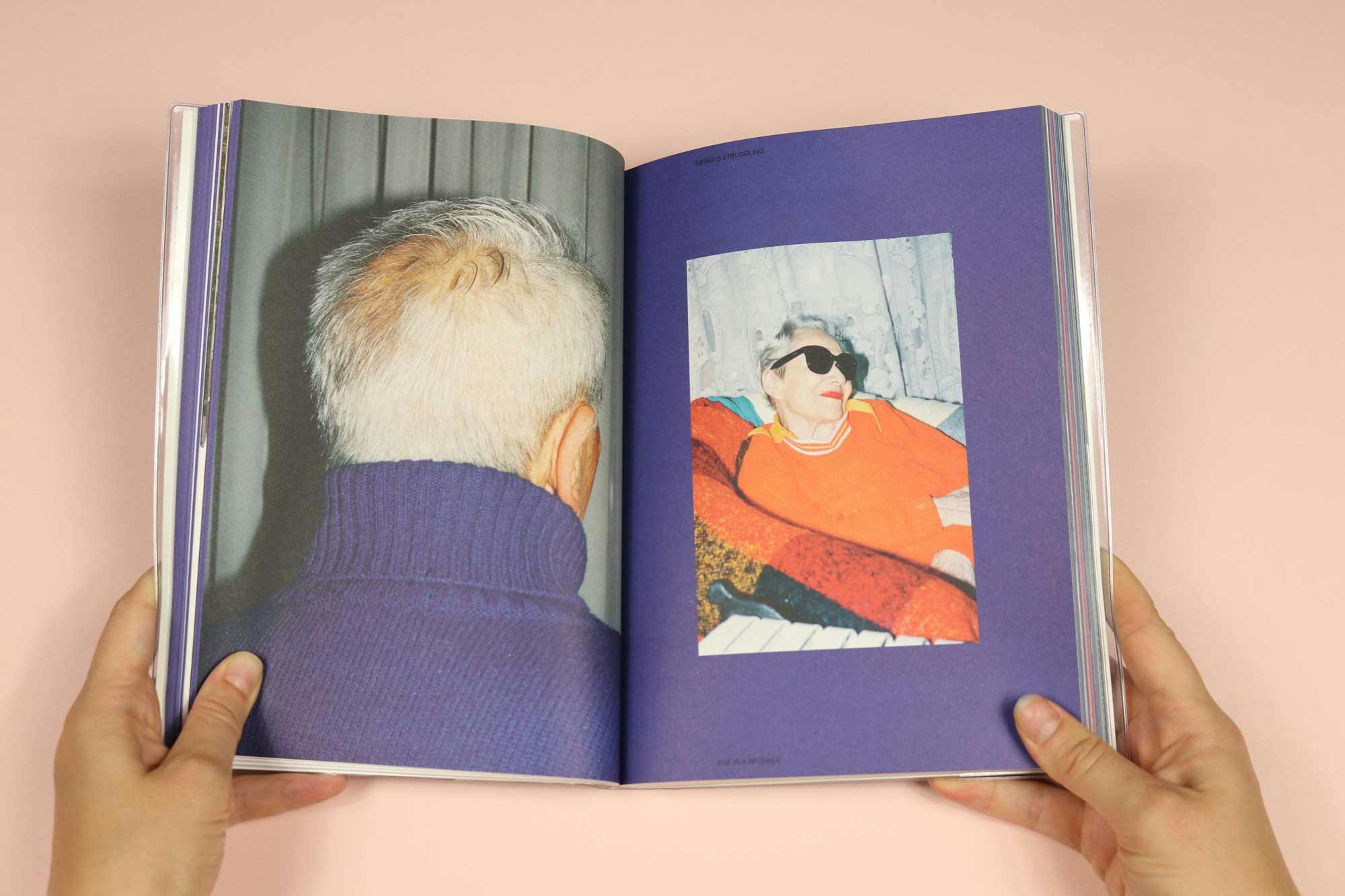

You include a photo-feature of elderly people called ‘Age is a Wrinkle’. It’s a different look at the passing of time, avoiding cliches. What did you want to avoid?

Instead of romanticising frailness and exploiting weakness, the photographer Nikita Dembinski believes that ageing itself is the mere process of inscribing just another wrinkle onto one’s physical body. The series explores the mundane so bluntly: everyday life can be lived regardless of this scary yet inevitable process that we are all undergoing: the uncontrollable passage of time.

One of our favourite pieces in the issue is by Ola Korbanska, who writes about her cleaning job, and cleaning as an act of protest. Why is cleaning a ‘gentle protest’?

Besides its utilitarian value, cleaning public spaces is a performative gesture: it is embedded in hierarchical power relations, as the job of dealing with dirt falls to those lower in class, gender, and ethnic hierarchies. Cleaners are most likely to be women or migrant workers. The piece was part of the ‘Purity is temporary’ project (2018), which explored cleaning as a cliché female activity, but one that eventually ends up becoming a form of protest against patriarchy. The action is gentle in its essence: quiet, nonviolent, even beneficial; it is about taking care. As part of the exhibition, the dirt collected from public spaces was used as a material to dye cleaning clothes, and exposed on large-scale banners with a message: “no woman no kraj!” (where kraj means country in Polish). That is why, rather ironically, a “gentle” action became an act of resistance.

This line from a piece about disused football stadium is interesting: “Slowly it became one of many decayed post-communist landscapes, a fenced area, full of garbage and post-apocalyptic flora, a place completely disconnected from its users.” Can you explain the significance of disused public space and its link to post-communism?

After the intense waves of privatisation that followed the fall of communism, many public spaces that were intended originally for the public were left behind in disarray. It is just another outcome of the neglect the public sphere has suffered from in the last three decades. At the same time, we are aware of contemporary internet trends (such as ruin porn and the subsequent mechanisms of exoticisiation/glamourisation of collective traumas) and try and stay away from that. Exploiting these landscapes can draw the average reader and attract a wider audience, but it does so at the expense of providing a comprehensive view on the matter, as well as feeding into an agenda that does not do Eastern Europe justice. The interest in Eastern European architecture and/or public spaces is immense and we don’t condemn it, but we think that it should be engaged with more carefully, while bearing in mind the social and historical context under which these landmarks were constructed.

And finally, we loved the honesty of that tweet! Can you talk a bit about the struggle of making a magazine?

We have to go back to Mayakovsky’s take on the daily grind, which not coincidentally also sums up our own experience with what ‘making a printed magazine’ entails. There is this glamorous part that seems to be associated with the process of making it, of presumably helping some people feel represented, or even shifting the perception of others. But things are a bit more complicated than that. The easiest step is to make the first issue, the hardest part is to maintain and keep the project going.