The crucially missing dialogue of lesbian culture

You know when you meet someone new, and just have the most interesting conversation? Reading Lez Spread The Word was like that; on every page, I encountered a novel, interesting, and important perspective. Independent magazines often platform crucial discussions that aren’t seen elsewhere, and this wonderful publication about lesbian culture is filled with such topics — how police tackle LGBTQ hate crime, a condom for lesbians, discussions on being gay and Arab, the taboo of homosexuality in sports.

I learned so much from the beautiful bilingual title (the french edition starts from the flip side) that I knew I had to talk to co-editor-in-chief Stéphanie Verge.

The magazine starts with stories of people from around the world who have found freedom in Canada. I know there is a lot more work to be done, but do you think it is especially open there? If so, why?

Our country is far from perfect. But pluralism is important to many Canadians — the idea that there is strength in diversity is championed by politicians, business leaders and other citizens. One of our prime ministers, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, became famous when he was Justice Minister for uttering the words “there’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation.” That was in 1967, and he was proposing amendments to the Criminal Code to push back against laws forbidding homosexuality.

Two years later, homosexuality was decriminalised. Same-sex adoption has been legal to varying degrees, depending on the province, since 1995. Canada was the fourth country in the world to allow same-sex marriage. These are all things we can be proud of, and they have helped build Canada’s reputation as a safe haven for LGBTQ+ people. That’s why women are choosing to move here to start over, to marry, to have children, as we touched on in the first issue of our magazine.

What was missing in the existing dialogue around lesbian culture that the magazine wanted to add?

Frankly, it’s not what’s missing from the dialogue, but rather that the dialogue itself is missing. There’s very little out there in terms of media for women who love women. It’s natural for people to want to see their stories reflected back at them and our magazine is filling a very clear need.

But speaking specifically to what kind of content we want to create, we are focused on highlighting positive role models — we want to celebrate queer women who are doing or have done bright, brave, ambitious things. When it comes to tough topics such as police response to homophobic crimes or the lack of safe sex between women, we want to help provide solutions whenever possible. In terms of the packaging of LSTW, we are committed to offering readers a beautiful product, a kind of coffee-table book that can serve as an archive. There have been a few influential magazines for lesbians over the years, but we’re determined to be the best looking!

You managed to profile some amazing women, from the former Icelandic PM to Tegan and Sara. Was it difficult to get in touch with these individuals and interview them?

Jokes are made within and outside the lesbian community about how interconnected we all are. There’s a certain truth to that stereotype and we’re using it to our advantage. Both the interview with former Icelandic Prime Minister Johanna Sigurðardottir and the interview and cover shoot with Tegan and Sara were made possible due to our connections.

In the case of the former, our publisher, Florence Gagnon, was invited to attend a gala in Montreal at which Sigurðardottir was being honoured, and she went over to introduce herself. We hadn’t yet put out an issue so there was nothing tangible to pitch, but Florence’s enthusiasm piqued Sigurðardottir’s interest. We mailed her a copy of the magazine when all was said and done and she sent us back a lovely thank-you note.

As for Tegan and Sara, they are Canadian and close in age to just about everyone on our team, so it was inevitable we would know some of the same people. Our official connection was Emy Storey, Tegan and Sara’s artistic director. She’s based in Montreal and she vouched for us with the band. Having them on the cover was a coup and a boon. And we can’t deny that their LSTW-related tweets and Instagram posts have helped us sell copies.

I noticed how the personal stories were credited with full names. Do you think it’s important to put a face behind the writing, so readers out there feel like they have a concrete role model?

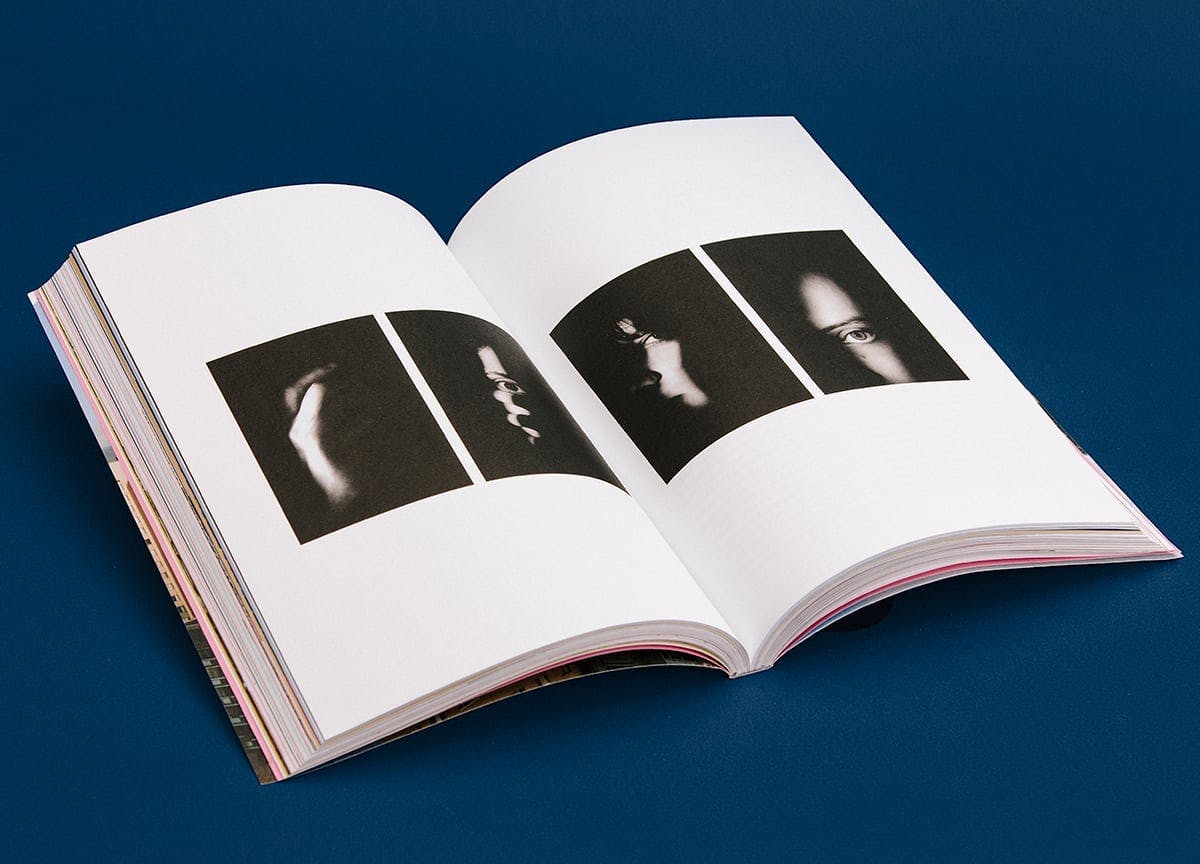

Definitely. Being a role model is much easier if you’re open. One of our goals is to combat queer invisibility and that’s only possible if our subjects are visible. That said, there is one exception in our first issue. We ran a piece about the women of Helem Banet, the women’s branch of an organisation that supports Arabic-speaking LGBTQ+ individuals in the Montreal area. In their case, we kept both their full names and faces obscured. It was out of respect for the women, who were putting themselves at risk. They weren’t necessarily in any physical danger, but there was a great deal of concern that their families would reject them if their identities were revealed.

I thought the article where police services talked about how they tackle LGBTQ+ hate crime was super informative. Were there some stories that were really difficult to tell?

Our excellent and very determined co-editor-in-chief, Claire Gaillard, wrote that particular article. There were complicated logistics involved because she was dealing with big, oft-criticised organisations, so it certainly wasn’t a story that could have been pulled off at the last minute. The Helem piece was complex due to the need for anonymity, so the photographer had to figure out a way to shoot the subjects without revealing their identities. Her solution — showing slivers of their faces — was quite elegant (below).

—

If you like independent magazines, we send out a different, surprise one every month — sign up to Stack to see for yourself