Ukraine and ‘sorrowfuturism’ in Kajet Journal

Like lots of other people I’m finding it hard to think about anything other than Russia’s invasion of Ukraine at the moment, so this weekend I picked up Kajet, the magazine that describes itself as, “a journal of Eastern European encounters”. Looking out across Eastern Europe, it proposes philosophical, playful and provocative new ways of seeing a region that is generally regarded as being a little bit behind the West – a place stuck out on the edge of the continent and struggling to emerge into its promised post-Soviet future.

I’d already had a quick read of the issue a few days before that, at the start of last week. At that point thousands of Russian troops were massed on Ukraine’s borders and warnings of invasion had been in the news for weeks, but still it just didn’t seem like something that could actually happen. I read the magazine totally convinced that Russia would never launch a full-scale invasion on its neighbour, but when I returned to it for a second time, the impossible had happened and things looked very different.

The latest issue of Kajet is themed ‘Easternfuturism’, a re-imagining of Eastern Europe inspired by the speculative optimism of Afrofuturism, and proposing a wide range of alternative futures for Eastern Europe. In their editors’ letter Petre Mogos and Laura Naum ask, “What types of thinking and practices are needed to re-imagine the future of Europe and Eastern Europe, alike? Is a new mode of thinking possible beyond ‘the end of history’ or after ‘the end of post-communism’?”

I suppose that on my first reading I did basically believe that we were living in a time after the end of history, with good old Western liberal democracy helping us to get by without waging war on each other. Now I don’t think Vladimir Putin has single-handedly taken us back to the middle of the last century, but he has definitely shown that he has no respect for liberal democracy. Again, that’s not a great shock, but the horror of waging war on Ukraine makes his disdain for our way of living completely unavoidable.

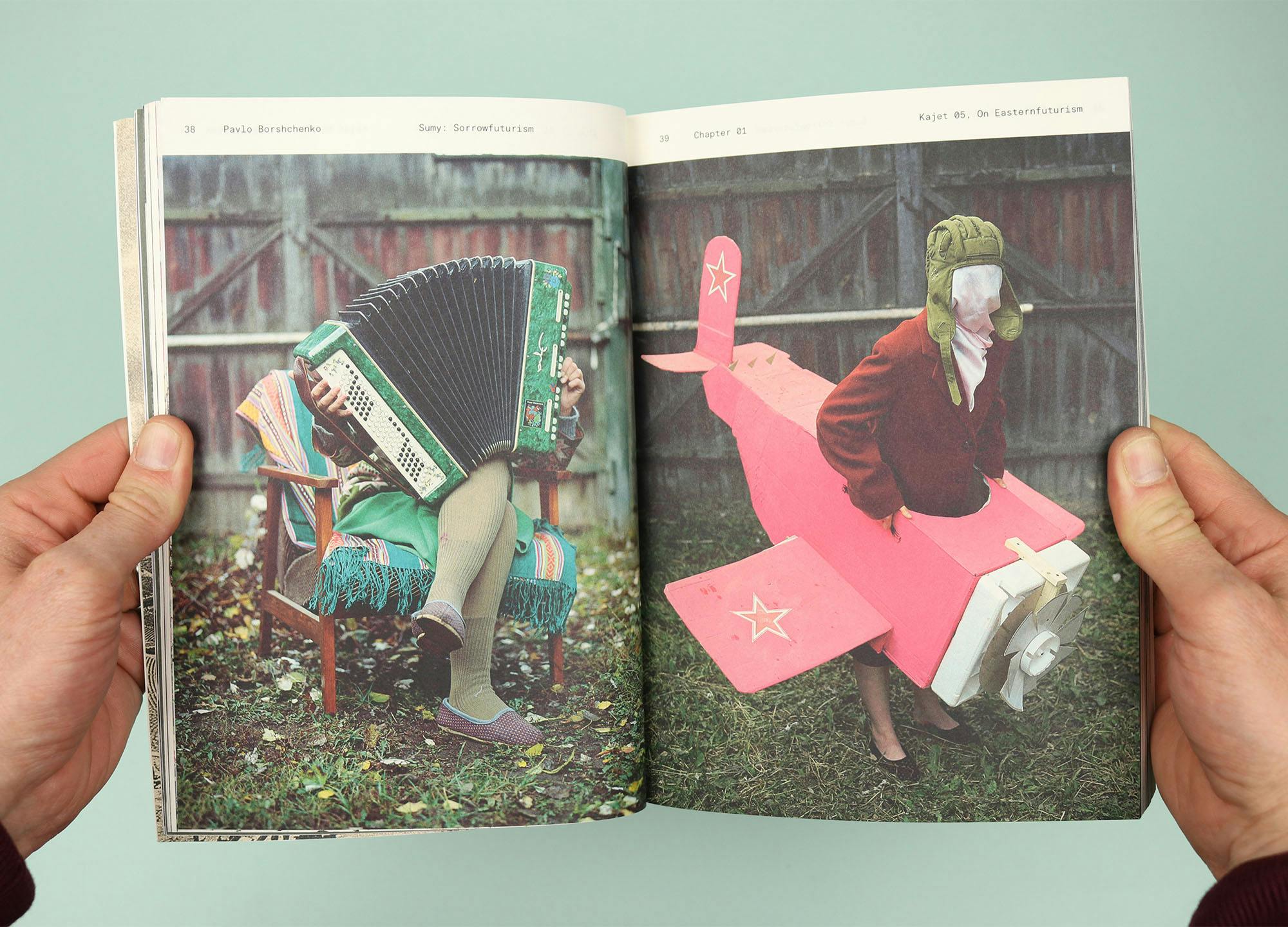

Seen in this harsh new light, several of the stories in Kajet take on a different meaning. For example the cover of the issue features a picture by Ukrainian photographer Pavlo Borshchenko, taken from his series Sumy: Sorrowfuturism. Sumy is the name of the city where he grew up in north-eastern Ukraine, and it was the scene of one of the first battles when Russian forces crossed the border.

In Borshchenko’s work, ‘sorrowfuturism’ is a way of expressing the experience of the generation born during the collapse of the USSR: “What does ‘Soviet’ mean for people who never lived in the Soviet Union but experienced its aftermath? Can this ambiguous idea of Sovietness be reclaimed, given that its symbols are in perpetual limbo, being everyone’s and, at the same time, no one’s?” Filled with faded relics of the utopian Soviet dream, rendered with kitsch charm and a gentle sense of humour, it’s presented as, “a place whose future used to be bright and whose best time seems to be in the past.”

It’s unthinkable that the people of Ukraine are now having to fight for the right to live in their own country under their own control, in a state that will surely be changed forever. Petre and Laura end their editors’ letter with a series of questions: “Can we disentangle ourselves from the traps of capital, from globalising and homogenising narratives that shape our imagination? In the context of disintegrating dreams and prospects, the failure of traditional liberal ideology, the rise of extremism and neo-fascist movements, the danger of profound environmental crises, and the dilemma of the nation state as a relic of the past, what does the future entail?”

All of those questions are as pressing now as they have ever been, but suddenly the nation state doesn’t seem like such a relic. Whether it’s Ukrainians risking their lives to fight for their land or Russians risking arrest to protest against the war, the nation state is surely much more relevant than it was at the start of last week.