What does it mean to be a man?

Masculinity has been in crisis so long it’s a cliché; every media outlet going churns out intermittent think-pieces about the hopelessness of it all, and the figures — like the fact that suicide is the leading cause of death for men under 45 in the UK, or that one in five women will experience sexual assault in their lifetime — are repeated so often, and so mechanically, it’s like we can’t compute them.

Three independent magazines currently have issues out that completely rewrite what it means to be a man today. But their most surprising achievement is that they’re not boring — coming in the midst of a content overload, they feel alive. Anxy, a California-based magazine dedicated to inner worlds, shares painfully personal stories of trauma and abuse, while Berlin-based Sofa prints difficult conversations between men verbatim, many of them trying to work through, and sometimes clumsily excuse, their culpability for #MeToo. The most novel approach comes in Johnny, a fashion magazine from Amsterdam that takes ‘plasticity’ as the theme for its latest issue, focusing on the potential for fashion to help men change who they are, because clothes offer “endless permutations of the self”.

All the models in the magazine are referred to as ‘Johnny’, suggesting the power of clothes to free you from the illusion of fixed, infallible selfhood, and where the lads’ mags of the early 2000s were a space to shore up male identity with ‘man’ things like chunky watches, embarrassing accidents and High Street Honeys, Johnny is part of a new wave of independent print proposing something like collective emasculation: hacking away the old ideas of what it means to be a man so that something new and more interesting can grow in its place.

Editor Aidan Connolly tells me he had the flattened personalities of the boys he grew up with in Australia in the back of his mind while making the issue: “It’s this shyness about even appearing as a person, because you don’t know what will lay you open to violence,” he explains over the phone from Melbourne. “What I found strange in them was also something others have found strange in me.” Growing into a man — in his experience — required erasing anything about himself that might come across as exceptionable. In response, Johnny documents self-expansion; a moving towards something more free.

It’s this commitment to experimentation, to running with an idea — however private, or wild, or confused — and following it through, that makes these issues cut through the noise around masculinity. That’s down, in part, to the fact that niche print doesn’t think twice about self-publishing things that would get mainstream outlets sued: in one article, Sofa describes the Rolling Stones as “drug addled war lords,” culminating their “rape [of women? the music industry?], as most successful man devils do, with the corporatization of their pillaging”. It’s a publication shot through with funny, often awkward nuggets, my favourite being the revelation that post-9/11 was a golden era for porn, because all the federal prosecutors who were working on obscenity cases got transferred to Homeland Security, so suddenly no one was policing the porn industry.

There’s a particularly strange piece at the end of the magazine called ‘Slut Watching’, about two men who like to lurk outside university halls to watch women as they do the ‘walk of shame’ in the morning. The illustration is a big red girl monster oozing liquid (liquid shame?) and the content is offensive: “women are most feminine when they’re vulnerable”, says Mark, the chief lurker, “Like dogs are the most canine when they’re lying on their back.”

I read it as fiction, a kind of pastiche of chauvinism, but it’s actually a true story. The writer befriended Mark (that’s his real name by the way), and actually spent days watching women this way. “What kind of magazine would publish this?”, Mark is quoted asking at one point, “It’s too controversial. It could be construed as misogyny.” That reads like a statement of editorial intent; female publishers Ricarda Messner and Caia Hagel created this issue after a weekend spent holed up with a group of men in the German countryside, and they say they didn’t want the magazine to exist in some kind of politically correct bubble.

“If you’re not being provocative then why are you even there? We wanted an arsehole piece. This is something that’s really real for a lot of men. If that dialogue never sees the light of day it gets deeper and worse.” You might argue that we’re already exposed to enough of this kind of misogynistic dialogue, but ‘Slut Watching’ is a piece that stays with you. There’s value to doing something that goes beyond the woke back-scratching of a Gillette ad.

Indie print might also be uniquely capable of addressing masculinity because of its intimacy. Editors aren’t gathering material for money, or clicks — it’s something personal. Anxy’s founder Indhira Rojas writes in her editor’s letter that this issue is inextricably bound up with her experience as a survivor of sexual abuse: “Reflecting on masculinity floods me with memories of grief and anger. Anger at the man who, in his position of authority, used his power to take advantage of a young child to satisfy his needs”.

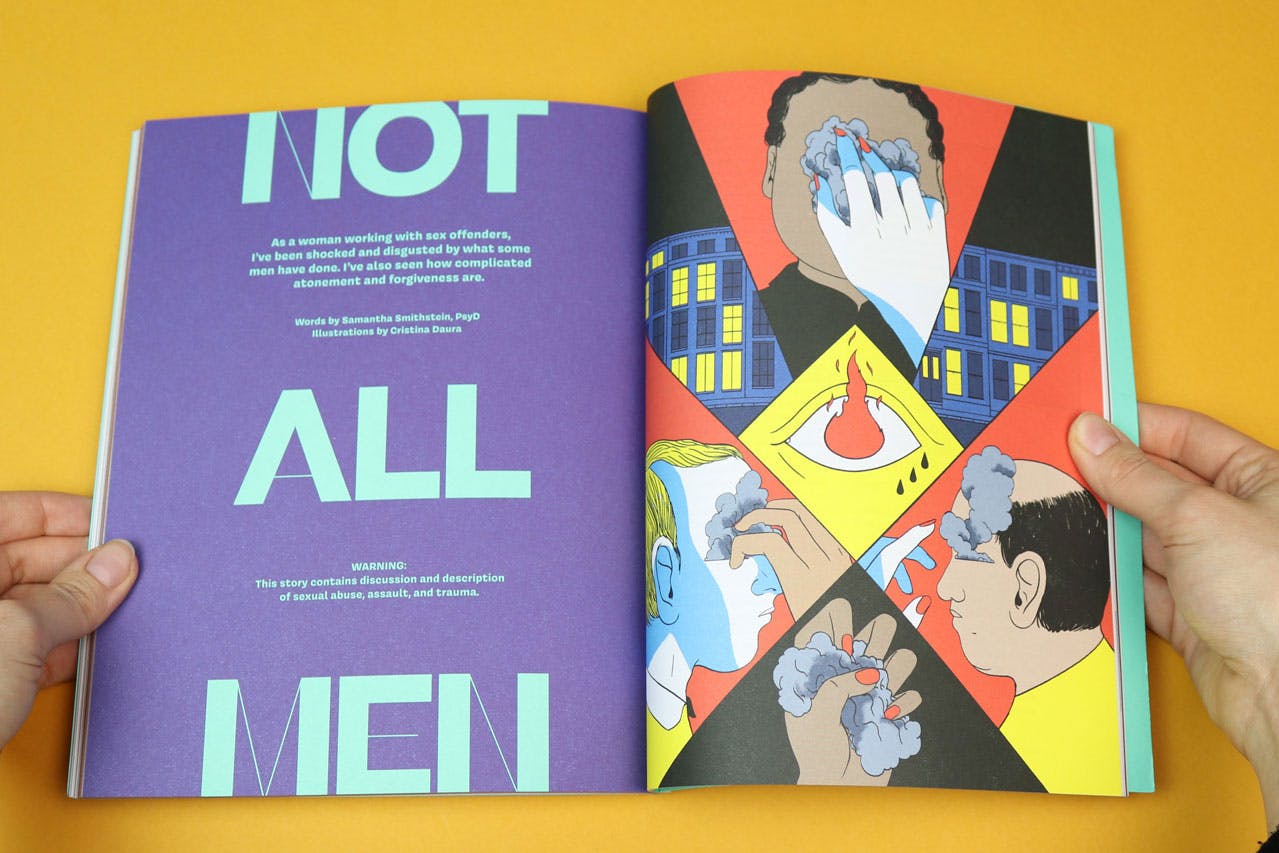

Later in the issue there’s a story about a woman who performs therapy with sex offenders. It’s a difficult read — at one point, the author recounts how a man starts to masturbate as he describes the things he’s done (“I was born hung… I can stick my magic wand in them.”) What this piece is really about, though, is the possibility of redemption — about the fact that most sex offenders are men raised in “a horrible system – frequently having suffered trauma, or abuse themselves”. The empathy and bravery it would take to publish a story like that as a survivor is very moving.

Threads of pain and partial resolution run through Anxy’s issue: a paramedic deployed to Afghanistan writes about his feeling that he didn’t do enough to help the soldiers in his care; a visual feature about rage and catharsis in a teen skate community in the Appalachian mountains is couched in the photographer’s need to work through her own violent upbringing. You feel, palpably, that it costs contributors to share like this, but that they must. Opening people up to their vulnerability is something every issue of Anxy tries to do, but it’s particularly important, Indhira tells me, in the context of masculinity. “To me that’s what is so beautiful about this issue: to witness the complexity of emotion experienced by men, who in my case, I often feel so fearful of.”

Ultimately, what’s most remarkable about these publications is that they are hopeful. About the possibility of unravelling ideas of manhood and beginning again. Johnny’s editor’s note talks about fashion as an art form particularly able to rewrite masculinity because it’s very good at making people want new things, and want to be new things. The power to shape desire is something fashion has always had in common with magazines. Rather than telling us the same old stories of masculinity in crisis, crisis is reframed on these pages as a precious and unprecedented opportunity for change.

The Masculinities Collection is available via the Stack shop.

- Lead image credit: Stacy Kranitz; Rage, Rinse, Repeat; Anxy.